The first time I ever heard American Slang was in my freshman college dorm room, just a week or two from the end of school, on a gorgeous April spring day. Now, if I’d been a law-abiding listener, the wait to hear the new album from The Gaslight Anthem—their follow-up to 2008’s acclaimed The ’59 Sound—still would have been the better part of two months. American Slang didn’t officially hit the streets until June 15. But 2010 was maybe the golden age of album leaks, and as a broke college student with a budget for little more than gas and the occasional midnight McDonald’s run with my roommate, that fact was very good news for me. It also meant that American Slang, a bulletproof summer soundtrack album, got to serve as the bookend to my first year of college, and to all the anticipation I was feeling as four months of summer approached.

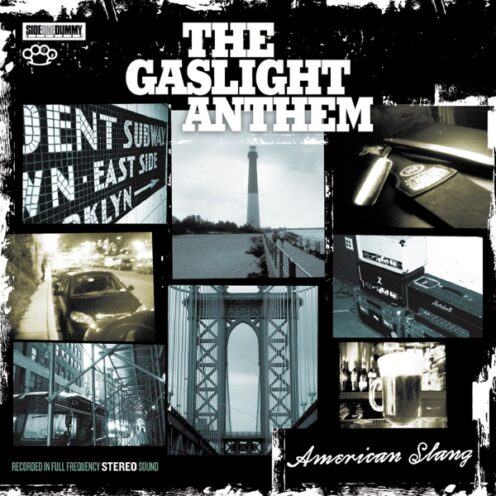

When The ’59 Sound broke in 2008, The Gaslight Anthem quickly became one of the most buzzed-about rock bands in all the circles I was a part of online. Here was a band that respected classic rock traditions and made them sound new again; a band willing to pilfer from their influences in the most loving manner possible; a band whose frontman was, perhaps, worthy of being called “this generation’s Bruce Springsteen.” All that hype only became louder and louder throughout 2009 and into the early part of 2010, which meant that by the time Gaslight announced their new record, excitement for it was through the roof. A title and an album cover that seemed to promise another sweeping classic-rock-styled masterpiece? Well, who could resist that?

The hype was such that, when American Slang hit the internet in April 2010, I had to break the campus internet rule of “no downloading” and pirate a copy. I showed restraint otherwise: the day American Slang leaked happened to be one of the most incredible windfalls of advance music ever to grace the internet. The events of that day are not well-documented—especially now that the forum archives of AbsolutePunk.net are gone—but for whatever reason, seemingly a dozen anticipated spring and summer releases leaked online within a matter of hours. It wasn’t just American Slang. If I remember correctly, that day also saw leaks of albums by The Black Keys, LCD Soundsystem, The Hold Steady, Band of Horses, The National, Josh Ritter, and Good Old War. But I knew if I was going to take the risk of getting written up for pirating music out of my dorm room, I was only going to chance it with one album, and that album was going to be American Slang.

It was a good choice. On first listen, I thought the 34 rip-roaring minutes of American Slang sounded like an idyllic youthful summertime. The moment the title track’s titanic guitar riff started issuing from my shitty laptop speakers, I wanted nothing more than to pack the car, turn up the speakers, and hit the road to home—toward another epic summer in my hometown, with high school friends I hadn’t seen or raised hell with in way too long. I was still two weeks away from that moment: from packing up the dorm room; from the drive fueled by anticipation that this would be the greatest summer of my life; from being able to call up all my buddies and hit up all our old haunts. But American Slang made it feel like that moment was already here. There was even a song called “Old Haunts,” even if it was telling me that those places from my past were “for forgotten ghosts.”

That’s the funny thing about American Slang in hindsight. I spent those first weeks—and indeed, that whole summer—treating it like a bulletproof summer soundtrack. It evoked, to me, the smell of rubber tires burning on blacktop roads or the feel of packed bars on sweltering summer nights. I heard it as a “we’re young and look at all these possibilities” record rather than as what it is, which is a “maybe we ain’t that young anymore” album. On The ’59 Sounds, the anecdotes of youth felt vivid and in-the-moment. Here, those stories feel like distant memories, washed away by time and age and incidence. The phrase “when you were young” (or “when we were young”) recurs repeatedly. “You’re never gonna find it/Like when you were young, and everybody used to call to lucky,” Fallon sings on “Stay Lucky.” On “Orphans,” it’s “When we were young, we were diamond Sinatras/Like something I saw in a dream.” And the closing track, simply titled “We Did It When We Were Young,” puts it plainest of all: “But I am older now/And we did it when we were young.”

The songs on American Slang often sound as raucous as anything The Gaslight Anthem ever recorded. See “The Spirit of Jazz,” where the drums pound so wildly and viscerally that they even, at one point, take over the song. See “Bring It On,” which sounds like a vintage Motown classic. See “The Diamond Church Street Choir,” where Fallon sings like a ’70s Van Morrison over the loosest rhythm-and-blues bed the band ever laid down on tape. But if you read into the lyrics, you start to see that this record is really about what happens when your youth dries up—when you’re left to settle into a period of your life where the magic, while still present, isn’t quite as noticeable or as electrically charged as it used to be. “The Queen of Lower Chelsea” is an ode to a girl who trades her tendency for going out and dancing late into the night for a stable full-time day job. On “Orphans,” Fallon looks in the mirror and sees someone with “aging bones,” ponying up to a fountain to drink the blood of his heroes. And repeatedly, the guy who spent The ’59 Sound quoting songs by everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Bob Segar to Adam Duritz, starts to question whether those songs still hold the promise he counted on in the old days. On “Stay Lucky,” Fallon talks about how “them old records won’t be saving your soul,” and he sounds almost matter-of-fact about it. By “Old Haunts,” he’s downright dismissive: “Don’t sing me the songs about the good times,” he bellows; “Those days are gone, and you should just let ’em go.”

10 years later, American Slang sounds a lot sadder than it did in 2010. Maybe it’s the change in my perspective, from staring down the summer that did end up being the greatest of my life to staring down 30 and knowing that those kinds of carefree seasons are a relic of youth I won’t ever see again. Or maybe it’s the fact that we now know the (presumably) full story of The Gaslight Anthem—a band that seemed like they were only getting started back in 2010, but that ended up running out of gas just four years later under the strain of burnout, broken hearts, and backlash. I would have bet money back then on these guys becoming the kind of stable, dependable rock ‘n’ roll institution whose legacy spans decades. Now, I’m not even sure if those kinds of rock bands can exist anymore. I can take solace in the fact that Fallon is living a happy life and is still making records—great ones, even. But every time I drop the needle on this LP and hear that same torrent of guitar that once filled my college dorm room, I can’t help but wonder what happened to this band, and to the fortunes they told us in American slang.

Old Haunts

Old Haunts