Between 2002 and 2009, Bruce Springsteen released five studio albums. Rather remarkably, that statistic made the aughts Springsteen’s most prolific decade ever. The Boss fired off four straight classics in the 1970s (Greetings from Asbury Park, The Wild, The Innocent, The E Street Shuffle, Born to Run, and Darkness on the Edge of Town) and put out four more in the 1980s (The River, Nebraska, Born in the U.S.A. and Tunnel of Love) before faltering in both quality and output in the 1990s. (The last decade of the millennium only saw Human Touch, Lucky Town, and The Ghost of Tom Joad, all of which are among Springsteen’s weakest LPs.)

The 2000s, though, brought the man back to life. Suddenly, Springsteen albums (and good ones) were a regular occurrence again. During the seven years that elapsed between 2002 and 2009, we got three E Street Band records (The Rising, Magic, and Working on a Dream), one acoustic album (Devils & Dust), and one tribute record (The Seeger Sessions). Four of those five records are worthwhile (Working on a Dream is the dud), and two are genuine classics (The Rising and Magic both recapture the…well, “magic” of the E Street Band’s golden age). However, there’s still an argument to be made that the three best Springsteen albums of the 2000s weren’t even written by Bruce, but by guys named Brandon, Craig, and Brian.

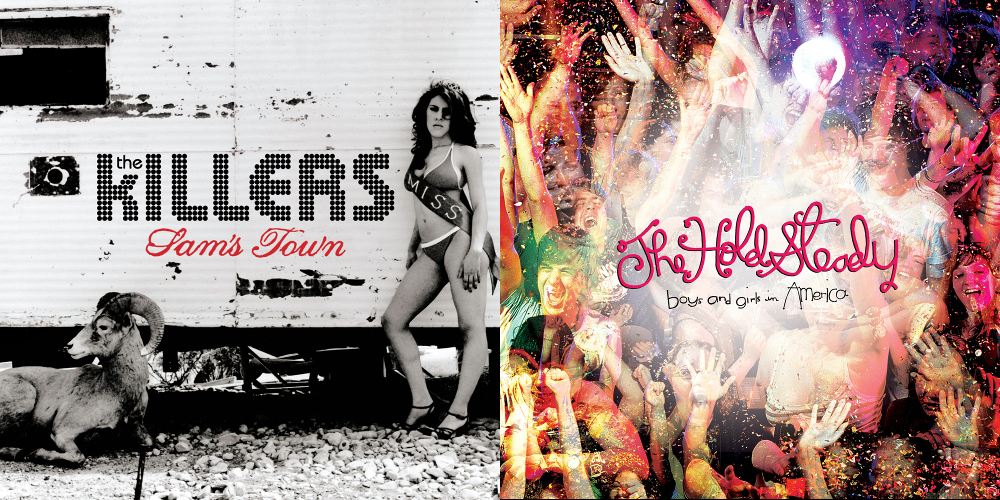

The three records I’m talking about are The Killers’ Sam’s Town, The Hold Steady’s Boys & Girls in America, and The Gaslight Anthem’s The ’59 Sound. All three albums are unapologetic classic rock throwbacks, all pair the bar-band swagger of the E Street Band with a lyrical style that mirrors Springsteen’s poetic romanticism, and all capture different geographical locations that have, at some point in time, been associated with the Boss. The ’59 Sound is the boardwalks of the New Jersey shore; Sam’s Town is the rural American heartland; and Boys & Girls in America is the long highway that stretches out between them.

All three of these records arrived within two years of one another. Of the trio, The ’59 Sound is the odd man out. The Gaslight Anthem’s breakthrough record draws most of its inspiration from the ’70s batch of Springsteen albums. The lyrics and overall vibe recreate the shaggy summertime romanticism of The Wild, The Innocent, The E Street Shuffle, while the album definitely has some of the epic sweep and aching hope of Born to Run. There’s also a little bit of darkness lurking out on the edge of town in those songs, but it hasn’t swept in just yet. Frontman Brian Fallon would get to that darkness on later album, but here, he still had an almost anachronistic faith in the power of rock ‘n’ roll.

The ’59 Sound also dropped in 2008, while Sam’s Town and Boys & Girls in America both arrived in 2006. Not only did Sam’s Town and Boys & Girls share a year, though, but they also shared a day. The Killers’ sophomore record and The Hold Steady’s third LP both bowed on October 3rd, 2006 for then-traditional Tuesday releases. It’s fitting that these records came out on the same exact day, because they play like two sides of the same coin. To be more accurate, they play like two sides of Springsteen’s The River.

For years, The River beguiled me because of its sprawl and seeming lack of cohesion. I loved the songs—almost all of them—but I didn’t understand why Springsteen had essentially tossed two very different records into a blender and made them into one oversized double album. He could have very easily divided the album into a daytime record (the loud, joyful, rambunctious, tipsy, and sometimes sleazy bar-band rockers) and a nighttime record (the desperate ballads, sung by broken-down heroes somehow still retaining their hope). It was only this year, when I saw Bruce and the E Street Band put The River through its paces at a live show, that I began to understand that the light only makes the darkness more effective.

If you were to split The River off into its moody extremes, though, then Boys & Girls in America and Sam’s Town are probably something along the lines of the albums you would get. For a start, Boys & Girls in America captures the spirit of bar band rock ‘n’ roll probably better than any record released since The River. Pitchfork’s review of the record even says that the advance copy of the record came with a coaster.

You can count on one hand the albums that sound more like summer than Boys & Girls in America, which kicks off in a swirl of radiant keys and roaring guitars and never lets up. (The song that does it, “Stuck Between Stations,” is a contender for best opening track of the 2000s.) The Hold Steady have always been regarded as a Springsteen-indebted band, but on this record, they legitimately sounded like they were broadcasting directly from E Street. The keyboards put the gas in the car, just like Roy Bittan’s elegant and wistful piano lines always do. The guitars light the ignition, just like the E Street Band’s three-guitarist attack always does. And Craig Finn, the band’s literate frontman, opens the record by quoting Jack Kerouac. That’s significant, seeing as the New York Times just credited Springsteen with injecting “more drama and mystery into the myths of the American road than any figure since Jack Kerouac.”

In the 11 songs that make up Boys & Girls in America, Finn scrawls stories of characters that spend the summer drinking, getting high, gambling on horse races, almost drowning in the Mississippi River, getting fucked up at music festivals, and drinking some more. The people in these songs constantly live by a mantra of massive nights, full of hazy remembrances and bad decisions. Lyrically, Finn is more like Greetings from Asbury Park Springsteen than any other version of Springsteen. He’s wordy as hell, often trying to cram more ideas into a line or verse than actually fit there comfortably. He pulls it off thanks to his dry bellow of a voice, which tended more toward spoken/shouted delivery on past albums, but which got a bit of extra melodic heft on Boys & Girls.

In terms of themes and characters, though, Boys & Girls reminds me a hell of a lot more of The River’s cheerier songs. The characters in these tunes know that they are never going to have a lot of money—even if they can win a few horse racing bets off the pointers of a clairvoyant girlfriend (as they do on “Chips Ahoy!”). What Finn’s characters have in common with Springsteen’s River protagonists, though, is that they don’t really give a damn about the fact that they’ll never be rich. The dark side of The River is about the characters who get trapped in their own lives, closed in by circumstances and unable to chase their dreams, until they snap. The light side is about the days before things go bad, when nothing sounds better than a rowdy summer block party with friends (“Sherry Darling”) or fantasizing about a pretty girl (“Crush on You”). Boys & Girls in America isn’t entirely free of angst, but the characters are able to find hope, life, and vibrancy in their own little escapes—whether they’re fleeing to a music festival for their “first day off in forever, man” (“Chillout Tent”) or hanging out at a shopping mall as the sun goes down (“Southtown Girls”).

Sam’s Town may have been the “bigger” October 3rd release and probably the first that most people listened to, but it’s actually more effective if played immediately after Boys & Girls in America. If Boys & Girls is Saturday night at the bar, Sam’s Town is the hangover. It’s the record where all the fears and failures you drowned in pints of beer and scorched with joints of weed come back to haunt you twice as hard because of the pounding headache in your skull and the bleary-eyed memories of all the mistakes you made the night before.

Sam’s Town was and is the darkest Killers record—which is saying something, since Hot Fuss is anchored by two parts of a “murder trilogy.” There’s a lot of desperation in these songs, a lot of yearning for escape and dreams left untapped. In some ways, Sam’s Town could be read as a concept record. Killers frontman Brandon Flowers wanted to chronicle his path from small town Mormon boy to big time Vegas rock star, and this album was his way of doing it. As such, the record dwells fairly heavily on themes of failure and stagnation. The title track opens the record with the lines “Nobody ever had a dream ’round here,” and goes from there, chronicling Flowers’ attempts to escape from his pent-up religious upbringing and find something more.

Famously, Springsteen’s characters are also small town blue-collar dreamers. Born to Run is all about those people finding a way to get out of their boxes and find bigger things. By The River, though, the characters who never got out have started to accept the fact that they probably never will. Sometimes, that realization drives them mad, as with Baltimore Jack in “Hungry Heart,” who leaves his wife and kids behind in a fit of midlife crisis, or “Stolen Car,” where the protagonist actually starts stealing cars to feel alive again. Other times, the heroes hunker down and accept their fate, as in the title track. Always, though, these characters cling to what’s left of their dreams, with the hope that someday things will change.

For Flowers, things obviously did change. He got his moment and then some. But Sam’s Town is still heavy with the fear, doubt, and regret of dreams left unlived. “I never really gave up on getting out of this two-star town,” Flowers sings on “Read My Mind,” a song that chronicles the fracturing of a teenage relationship and makes it a parallel for the shattering of an escapist dream. “For Reasons Unknown” and “Uncle Jonny,” meanwhile, are songs about the people who never got out—the former about Flowers’ grandmother and her battle with Alzheimer’s, and the latter about an uncle with a drug addiction. The message, ultimately, comes full circle in “This River Is Wild,” one of the record’s big climactic numbers. “This town was meant for passing through,” Flower sings in the verse, before getting to the key line at the start of the chorus: “Better run for the hills before they burn.” Better hit the road while you still can, in other words, lest the years fall away and leave you like one of the characters in your songs.

Ultimately, Flowers finds the light at the end of the tunnel. The album’s de facto closer—the massive, string-assisted “Why Do I Keep Counting?”—finds the protagonist of the record leaving his small town behind in pursuit of something else. He’s not sure where he’s going or where his dreams are going to take him, but he’s found something to live for again—just as the hero of Springsteen’s The River remembers never to take anything for granted in that album’s final song, “Wreck on the Highway.”

For two albums that came out within a day of each other and share so much of the same inspiration, the reactions to Sam’s Town and Boys & Girls in America could hardly have been more different. Boys & Girls was largely heralded as an indie rock masterpiece, earning a 9.4 and a Best New Music badge from Pitchfork, an 85 on Metacritic, and several EOTY list notices—including Album of the Year honors from The AV Club. The album was praised for being “unafraid of cliché,” for “having something to say,” for being the band’s Born to Run, and for being the kind of record that the characters in Craig Finn’s songs would love to listen to. By all accounts, the reviews for Boys & Girls in America anointed it a masterpiece, and the Springsteen influence wasn’t downplayed or derided, but praised and labeled as refreshing.

Sam’s Town didn’t get the same praise. Though the album got enough positive reviews to salvage a 64 on Metacritic, the reception was the definition of mixed. The album received particularly dismal write-ups from noted publications like PopMatters, The New York Times, and Rolling Stone. For someone who followed the rollouts for both Sam’s Town and Boys & Girls in America, it would have been nearly impossible to miss how ironically incongruous the reception of the two records really was. Sam’s Town was ridiculed as the sound “of a young band overreaching”; it was criticized for its “hackneyed clichés” and “pandering melodrama”; it was called a “cluttered, derivative mess.” Flowers also received the ultimate music critic slap in the face, with Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone proclaiming that he was a guy with “nothing to say.” The Springsteen influence wasn’t missed or downplayed here, either, but instead of being seen as refreshing and praiseworthy, critics made it their punchline. This band channeling Springsteen was all about bluster and histrionics, with maybe a little bit of downright plagiarism thrown in along the way.

10 years later, the cultural places that these two records occupy don’t seem so different anymore. Boys & Girls is still beloved—especially among fans—but The Hold Steady aren’t “cool” anymore. Most critics have written off the band’s last few albums for being too conventional, too pared down lyrically, and too overproduced. Teeth Dreams, their 2014 LP and still their most recent, didn’t sound so far from the sonic territory The Killers mined on Sam’s Town. Boys & Girls will get a 10-year tour this fall, and fans still consider it a classic, but among the Pitchfork crowd, the record doesn’t seem to float on the same cloud as other mid-2000s BNM winners, from Arcade Fire’s Funeral to Sufjan Stevens’ Illinois.

Sam’s Town, meanwhile, has only grown in the estimation of most fans and writers. Rolling Stone’s readers tried to apologize for Sheffield’s over-the-top two-star pan in 2009, voting the album the most underrated record of the 2000s. (Rolling Stone even deleted Sheffield’s review from their website, evidently regretting his bluster in the long run.) Talk to a group of Killers fans, meanwhile, and Sam’s Town seems to get brought up as their definitive classic with more frequency than even Hot Fuss. In general, the record gets credit now for being something much darker, deeper, more complex, and more personal than most people thought it was in 2006.

The question is, why were these two albums that shared so much—from a key influence to lyrical themes to a release day—looked upon through such different-colored glasses? Why were The Hold Steady cool for adopting the bar-band vibe of The River while The Killers were inauthentic losers for channeling the angst and desperation of its darker songs? After all, it’s The River’s more emotional numbers—like the title track, “Independence Day,” or “Stolen Car”—that are most often listed as its finest.

There could be several reasons for the disproportionately opposite reactions. For one thing, Brandon Flowers did himself no favors in the lead-up to Sam’s Town, proclaiming that it would be “one of the best albums in the past 20 years.” The moment he made that statement, millions of people started rooting for him to fail. Secondly, while The Killers and The Hold Steady definitely both pivoted to a more anthemic sound with their respective 2006 albums, Flowers and co. made the bigger pivot by far. Many fans—myself included—we confused upon first listen to Sam’s Town because it was such a far cry from the ’80s pop-driven sound of Hot Fuss.

Perhaps the most important difference, though, was the simple contrast in the bands and their public perception. The Hold Steady were a cool indie band that wrote songs about drinking and smoking weed and gave off the vibe of not taking themselves too seriously. (Fairly, an album as stacked with literary references and complex characters as Boys & Girls in America cannot be classified as the work of a band not taking themselves seriously.) The Killers, on the other hand, were one of the biggest bands in the world, embraced by radio and situated firmly in the mainstream. They were writing ultra-earnest songs about small towns, the American Dream, escape, and failure. Flowers reflected on his personal history, but he did it through a classic rock filter that made it seem larger-than-life to the point of becoming myth. For a lot of people, that myth-making streak seemed pretentious, but then again, no one has ever accused The Killers of not taking themselves seriously.

The loud Springsteenian bombast that The Hold Steady tried out on Boys & Girls in America wasn’t fashionable by the standards of modern pop or indie rock, but it was still cool in the way that record stores were cool. The Killers played a similar style of bombastic Springsteen-inspired rock, but they wore their hearts on their sleeves and aspired to follow Springsteen to the stages of arenas instead of accepting the limitations imposed on modern rock bands. They weren’t cool and still aren’t, but now that The Hold Steady aren’t “cool” either, it’s a lot easier to see these two albums as what they are: two classics that parallel and complement each other about as perfectly as any pair of records released in the 2000s. We’re lucky to have both.