There’s a song on the new Donovan Woods album Both Ways called “Next Year,” about the very-human tendency to put things off. “We’ll do it next year,” Woods sings—five words we’ve probably all spoken a time or two before. Those words could refer to a lot of different things, depending on your situation. They could be about a trip you’re going to take, or a renovation you’re going to do on your house, or something fun you’re going to do with your kids. Too often, though, next year never becomes this year. It’s just always next year, always tomorrow. And eventually, all those things you were going to do pile up and you realize that you’re running out of time to actually do them. That’s what happens at the end of the song, where Woods sings about an ailing father and his wish to see the Grand Canyon. Instead of making plans for later, the dad and his son just get in the car and drive. Because, as Woods states, “There ain’t no next year.” The sand in the hourglass is almost gone. It’s now or never.

It’s probably an odd maneuver to start an album review talking about the last song on said album—and to give away its big, tear-jerking plot twist, no less. But I needed to start with “Next Year” because it’s the perfect microcosm of everything that makes Donovan Woods such an incredible songwriter. It’s a song with a universal message, but it’s also not something we’ve heard before. We’ve heard songs about getting older, missing opportunities, running out of time. But I, at least, have never heard a song that addresses those subjects in this particular way. And these kinds of songs are, in my mind, the best songs. The ones that take things we all know about, but talk about them in ways that no one else has quite thought of yet. Those are the songs that have enough power and potency to make you look at the world differently, or to make you re-evaluate the way you’re living your life.

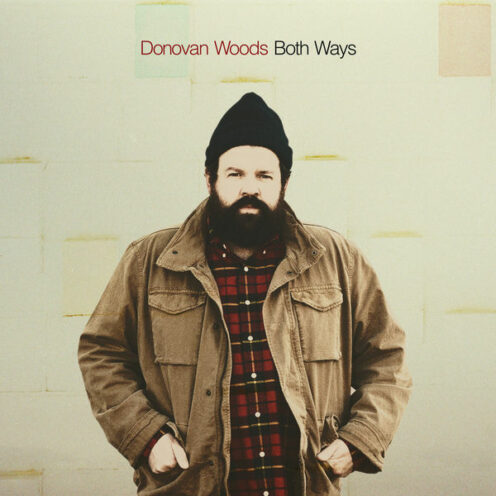

Donovan Woods has written those kinds of songs before, but he’s never put so many of them on one album as he does on Both Ways. It’s his most consistent, best-sequenced, and all around finest album yet. It’s also his most varied. Woods has always excelled at acoustic ballads, but he’s never made a song as big and bombastic as “Truck Full of Money,” or one that rocks quite as much as “Easy Street.” Even the acoustic songs have some flourishes that we haven’t heard from Woods before, like “Read about Memory,” which sounds like a radio broadcast from the distant past.

Even with the expanded palette, though, Woods’ best weapon is still his songwriting. He’s like a Canadian Jason Isbell, capable of giving his songs a wallpaper of details that makes them feel real and lived-in, but also possessing the killer instinct to twist the knife or deliver a gut-punch at the exact moment when it’s going to hurt the most. In “Our Friend Bobby,” he tells a tale about a childhood friend and next-door neighbor, a guy who grew up, became a fuck-up, and ultimately died in a maybe-not-so-accidental car accident. Late in the song, Woods describes how his friends talk about the titular character, playing up his antics, his wrong-side-of-the-tracks narrative, his bad side. “But when’s the last time any of them saw him or talked to him? He wasn’t that bad a guy,” sings Woods. It’s a sobering reminder of how the way we talk about people and remember them after they’re gone only represents a narrow slice of who they were. Again, it’s a song with the power to make you see the world a little differently. It gets you asking big questions like “How would people talk about me if I were gone tomorrow?”

Throughout Both Ways, Woods rarely raises his voice above a whisper. It’s a fact that makes his songwriting that much more remarkable, because he’s able to wring so much emotion out of the quiet grace of his words. He doesn’t need to take his songs through hair-raising crescendos to turn them into showstoppers, because the stories do the heavy lifting for him. That’s not to say it isn’t thrilling when Woods does play with dynamics. “Great Escape,” the album’s penultimate track, explodes mid-way through into a rare moment of chaos and catharsis in his catalog. But Woods also doesn’t need that big dynamic build to sell the unique ache of songs like “Another Way,” about a divorcee embarking on his second marriage; or “Burn That Bridge,” about letting yourself fall completely for a good friend, knowing there’s no way back; or “I Ain’t Never Loved No One,” a chilling duet with Rose Cousins, about bringing a significant other home to meet the family for the first time.

Millions of people should hear these songs. Millions of people should love these songs. Millions of people could love these songs. Woods has been in the game for a while now, and his talents haven’t gone unnoticed in songwriting circles. He’s written tunes for big Nashville stars like Tim McGraw, Billy Currington, and Charles Kelley, as well as for underrated up-and-comers like Charlie Worsham. So far, though, he hasn’t gotten the due he deserves for his own work—at least not in the United States. Both Ways provides the most compelling argument yet for why that fact should change. If there’s any justice, it will.

And if not now? Well, maybe next year.