The first time I heard 22, A Million, the long-awaited third album from Bon Iver, I hated it. To my ears, it sounded like a formless mess, devoid of any clear highlights (at least on the level of the best songs from Justin Vernon’s previous albums) and frequently undone by head-scratching production choices. Granted, I was listening to a shitty rip of a shitty stream that had leaked to the internet months in advance. I’d also had my expectations sent through the roof by live recordings of the band’s full playthrough of the record at this year’s Eaux Claires music festival. Even an amateur audience recording of the performance captured the magic of the new songs and made it sound like 22, A Million—despite arriving on five years’ worth of built up anticipation—was going to live up to my every expectation. Hearing the same songs in studio form didn’t hit me the same way, and I spent months considering 22, A Million my biggest disappointment of the year as a result. Even after the album officially released in September and I finally got to hear a full-quality version, I heard it as a distinct step down from its two predecessors.

As I’ve learned in the months that have passed since, though, 22, A Million is neither a record meant for first impressions nor a record meant for the season in which I first heard it. This record leaked at the end of August, during summer’s dying days, and absolutely zero things about 22, A Million say “summer.” Where 2011’s Bon Iver, Bon Iver sounded right at home on muggy summer nights, 22, A Million is meant for cold seclusion. My enjoyment of this album seemed to grow with every drop of a degree on the thermometer. By the time the first snow of the year fell, I had charted the full journey from “hate” to “disappointed” to “indifferent” to “grudging appreciation” and finally to “love.” It’s one of the oddest adventures I can ever recall taking with an album.

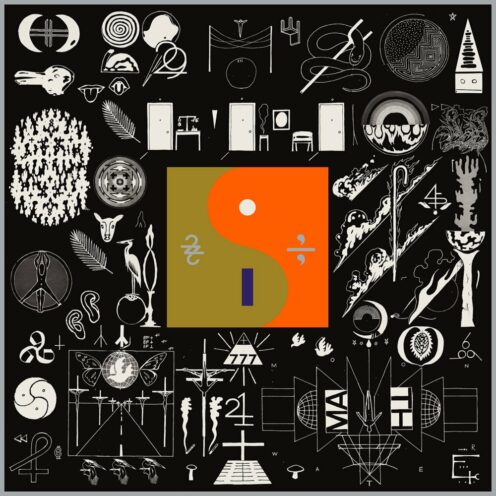

That distinction is fitting, since 22, A Million is something of an oddity on its own. (For proof, just try reading the track listing.) Everything from the weird song titles to the symbol-heavy album cover to the glitchy production seems designed to purposefully alienate listeners—or at very least, challenge them. The songs themselves are often challenging as well, veering further from the wintry cabin folk of For Emma, Forever Ago than Vernon has ever gone with one of his own projects. “10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⚄ ⚄,” for instance, sounds more like Vernon’s work on Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Yeezus than anything he has previously put on a Bon Iver or Volcano Choir record.

I firmly believe Justin Vernon has one of the greatest, most distinctive voices in the history of recorded music. His lower chest voice register is solid, capable of achieving deep booming baritone and bass ranges, but it’s with his falsetto that Vernon can level you. That facet of Vernon’s voice has always been his not-so-secret weapon. On For Emma, Forever Ago, it sounded almost otherworldly while still somehow conveying a heartbroken fragility that was thoroughly human. And while Bon Iver, Bon Iver expanded the sonic palette and pushed toward more ambitious arrangements, there was still a definite focus on Vernon’s falsetto and the melodies it carried. Looking back at my first few months with 22, A Million, I think the thing that I’ve struggled with the most is the way Vernon’s voice figures into these songs. Because of the push in a more experimental direction, it figures that much of this record would be less singularly focused on voice and melody than Vernon’s folk era. Add the record’s production—which frequently spits Justin’s voice through a vocoder (“715 – CR∑∑KS”), layers it with effects-laden harmonies (“29 #Strafford APTS”), pitches it up into chipmunk voice territory (“22 (OVER S∞∞N)”), or entirely overwhelms it in background noise (“21 M◊◊N WATER”)—and Vernon’s gorgeous falsetto only gets a few moments to take center stage.

On my early listens, I was especially thrown off by “29 #Strafford APTS.” On the live recording of the Eaux Claires show, “Strafford” sounded like it had the potential to be one of the greatest Bon Iver songs ever. With a gorgeous falsetto hook and a steady acoustic rhythm that made it sound like a not-too-distant cousin to For Emma’s “Blindsided,” “Strafford” was the song I was most looking forward to hearing in studio format. But where the live version was more or less straightforward, the studio version is layered so deeply in harmonies, pitch-shifted vocals, and distracting production flourishes (there is a deliberate glitch in the final minute that sounds like the tape cutting out) that it lost the subtle, unassuming beauty of the live version.

At least, that’s what I thought at first.

The more I listened to 22, A Million, though, the more I began to see what Vernon was going for. Made in the wake of a period of crisis, anxiety, depression, and confusion in Vernon’s life, 22, A Million embraces the beauty of being unsure. The first lines of the record are “It might be over soon”—as in, “the way I’m feeling right now might not last forever.” It’s the perfect start to the record, a record that sees Vernon on a journey to find himself again. In that context, all of the production choices—the chopped up or pitched vocals, the disjointed way in which some of the songs are stitched together, etc.—makes a lot more sense. These songs are literally the sound of a broken man putting himself together. Famously, For Emma, For Emma ago was the sound of the same thing. However, where For Emma found Vernon broken in the wake of a breakup, the wounds he’s healing on 22, A Million are more complex and more difficult to bandage. It’s fitting, then, that the sound of the record is more complex and less welcoming. While the production choices might have turned me off at first, they now strike me as a beautiful and vital part of the canvas. For example, surely a song like “715 – CR∑∑KS” wouldn’t ache quite the way it does if it were stripped of the vocoder and performed in a more traditional, folky arrangement.

With all of that said, there are still moments here where Vernon sounds like his old self. Though “22 (OVER S∞∞N),” is built on the foundation of a glitchy, chopped up vocal loop, Vernon still lets his falsetto be the eye of the storm. As the opener of the record, the song provides the perfect midway point between the comfortable familiarity of what Bon Iver has been in the past and the more adventurous, sonically experimental direction of this album. Songs like “666 ʇ” and “8 (circle),” meanwhile, don’t sound so far off from some of the material that made up the back half of Bon Iver, Bon Iver. And the album’s closer, “00000 Million,” feels like a homecoming, a piano-led beauty built like a church hymn. “If it’s harmed me, it’s harmed me, it’ll harm me, I’ll let it in,” Vernon sings, accepting that his troubles might not be over, but that he can’t run away from them either. It’s not a clean, neat resolution to the journey that he embarked upon in “22 (OVER S∞∞N).” But in real life, few things are clean and neat, and this album, with its evident scars, jagged edges, and meandering lost-and-found theme, reflects that fact perfectly.