Transatlanticism is my favorite album of all time. Death Cab For Cutie’s fourth album, released fifteen years ago today, is the band’s second concept album. Transatlanticism centers itself around long-distance love, with both its strengths and downfalls. Ben Gibbard, the band’s soft-sung lead vocalist, lyricist, and guitarist, penned the term “transatlanticism” to express the unfathomable emotional space between two young lovers. The distance Gibbard discusses feels impenetrable. Transatlanticism sees Death Cab For Cutie experimenting with soft-loud dynamics (“Transatlanticism”, “We Looked Like Giants”), perfecting the gorgeous quiet track (“Lightness”, “A Lack of Color”), and witnesses them pushing themselves to go all-out and produce the flawless pop song (“The Sound Of Settling”). Completing all of this is the efforts of guitarist, co-writer and producer Chris Walla. Walla’s lo-fi production is perfect for Transatlanticism. Fifteen years later, and Transatlanticism still sounds incredibly rich and indulgent, yet also warm and intimate.

Album opener, “The New Year,” is the first of many tracks to achieve the band’s main goal while working on Transatlanticism. Prior to the release of the album, Gibbard had this to say:

We’ve tried to construct it with transitions of songs going in and out of each other, and I think it’s a little bit more expansive than the last record.

Immediately, “The New Year” catapults listeners into Transatlanticism’s sweeping world, beginning with a rumbling train; ascending before the arrival of crashing guitars coupled with glowing, bright drumming. In “The New Year”, Gibbard recalls the absurdity of things like “New Year’s resolutions”, admitting: “so this is the New Year / and I don’t feel any different” then, in the second verse: “so this is the New Year, and I have no resolutions”. He also reminisces for simpler times, the periods where “the world was flat like the old days,” so he and his partner could travel to see each other by “folding a map.” Gibbard desires to rebel against distance, but instead, he, unfortunately, comes across as defeated.

Transatlanticism explores the agony and challenges of long-distance love further in its runtime, but why should I rush myself? After “The New Year” is the misleadingly beautiful “Lightness.” It’s the first track that encapsulates Death Cab For Cutie’s vision of having songs transition in and out of each other, as “Lightness” flows from “The New Year” in stunning fashion. You don’t even feel it. “Lightness” follows Gibbard as he attempts to create a convincing argument to remain faithful, but ultimately accepts that his thoughts of disloyalty go against what he feels is right. His voice quavers as he tries to strongly declare: “you shouldn’t think what you’re feeling.” It’s brutally honest, in turn making “Title And Registration,” the next track, increasingly heartbreaking.

Fun story: I was a foolish teenager who downloaded Transatlanticism from good old Limewire. The download didn’t include “Title And Registration.” I embarrassingly listened for months, not realizing a track was missing, a track I came to love dearly… Anyway, “Title And Registration” finds Gibbard in the devastating aftermath of a significant relationship breakdown. He rummages through the (incorrectly named) glove compartment, just to find “souvenirs from better times” – the souvenirs can be perceived as various trinkets his ex forgot in the car, as well as some photos. “Title And Registration” becomes more desolate when Gibbard recognizes that “there’s no blame for how our love did slowly fade.” Ben Gibbard is a master of capturing the beauty and ugliness of human emotion, as well as the full depth held inside the spectrum of human emotion.

Where Death Cab For Cutie seems to thrive the most is in the under-appreciated beauty, “Expo ‘86”. The track sees the band firing on all cylinders: a mellow start, an exciting chorus and bridge, descending piano, and a wonderful juxtaposition between melancholy lyrics paired with extremely catchy music. “Expo ‘86” delves into the toxicity of repeated cycles – “sometimes I think this cycle never ends / we slide from top to bottom then we slide and turn again”, and for listeners who struggle with anxiety as I have, Ben Gibbard captures the uneasy dread of our day to day lives: “I am waiting for something to go wrong / I am waiting for familiar resolve / I am waiting for another repeat / another diet fed by crippling defeat”. With “Expo ‘86”, Death Cab For Cutie assisted confused teenage-me in identifying issues I couldn’t voice yet. I’m not sure if the band knew that this song, as well as the rest of Transatlanticism, really, would be so very helpful for legions of fans years down the track. “Expo ‘86” gave me solace when I desperately needed it. For that, I am eternally grateful.

“Expo ‘86” isn’t the only song that makes use of a superb contrast between saddening lyrics and catchy music. “The Sound Of Settling,” a track Ben Gibbard initially disliked but was urged to leave on the record by Chris Walla (thank you, Chris), does it again. It’s a song that quickly turns out to be layered and huge. Opening with a pressing guitar, “The Sound Of Settling” is joined by Nick Harmer’s groovy bass line and Jason McGerr’s urgent drumming. For the first time, Transatlanticism is actually quite amusing, but still so sad: “and I’ll sit and wonder of every love that could have been / if I’d only thought of something charming to say.” It’s a tragic view of what life could be like if we didn’t take any risks. However, “The Sound Of Settling” doesn’t even come close to what the one-two punch of “Tiny Vessels” and “Transatlanticism” make me feel.

For a long time, I couldn’t listen to “Tiny Vessels.” It’s a song concerning unrequited love, but on the other side of things. It’s cruel. I do applaud Ben Gibbard for writing the song now; it’s gutsy and emotive, perhaps these stories need to be told, too. But, when Gibbard gently sings “this is the moment that you know / that you told her that you loved her, but you don’t,” I instantly lose it. I’m transported back to a specific, very painful time in my life where my first partner was unfaithful. I’m left wishing he could be as blunt as Gibbard is in this song. As hurtful as “and you are beautiful, but you don’t mean a thing to me” would be to hear, it’s better than the alternative I had to reckon with. Coupled with mournful, swelling guitars and an explosive climax, “Tiny Vessels” remains an emotional powerhouse to this day. Then, there’s the immaculate title track. “Transatlanticism,” to me, is Death Cab For Cutie’s musical and lyrical magnum opus. It opens on a tender note. For half the song, it’s just Ben Gibbard’s voice accompanied by the piano. It’s a tale of the woes of long-distance love – Gibbard is simply beaten here: “the distance is quite simply too far for me to row / it seems farther than ever before.” The overwhelmed nature of “Transatlanticism” isn’t here to stay, though. Before you even realize it, the track opens itself up, developing a romantic swirling experience of both catharsis and celebration. The percussion and piano combined are almost deafening – I can only imagine what it’s like when performed live. Simply and sadly, Gibbard murmurs, “I need you so much closer.” The despair takes over, and multiple voices join Gibbard, wailing, “so come on.” Since October 7, 2003, “Transatlanticism” has soundtracked countless long-distance relationships, including my own. Where “Tiny Vessels” breaks my heart, “Transatlanticism” encourages hope and the release of pent-up emotion.

Things get pretty interesting late in Transatlanticism, as “Passenger Seat” is the first happy song on the album. It’s solely Gibbard and a piano, and like “Transatlanticism” before it, “Passenger Seat” is majestic. Gibbard takes us on a road trip where he explores unconditional love. I can’t say for sure whether the duos he speaks of are soul mates or parent and child; you decide how you’d like to interpret it. “Passenger Seat” finds Gibbard feeling utterly safe and deems this person trustworthy: “with my feet on the dash, the world doesn’t matter.” This is a song of deep love and security. When Gibbard resoundingly declares, “when you feel embarrassed, then I’ll be your pride / when you need directions, then I’ll be the guide,” I can’t help hoping I can be that person for my partner, “for all time.” Transatlanticism’s final two tracks keep up the honesty and continue dissecting stories of love. Although, they couldn’t be any further apart sonically or in subject matter.

Transatlanticism is a mostly mellow album, until the exhilarating penultimate track, “We Looked Like Giants” begins. The song builds and builds, from opening with droning guitar to the blend of beautiful, melodic piano and steady drums, to all-out jamming. From the moment “We Looked Like Giants” bursts into gear, the band fight to keep the bombastic vibe of the track. “We Looked Like Giants” is incredibly sentimental, seeing Gibbard evoking memories of first love and first sexual experiences. He’s visibly infatuated, and can’t keep his excitement to himself as he croons, “I don’t know about you, but I swear on my name they could smell it on me.” Gibbard also reveals the wonderful feeling of sharing music you love with someone you’re smitten with, looking back with endearment: “do you remember the J.A.M.C. (The Jesus And Mary Chain, who Gibbard himself is a fan of), and reading aloud from magazines?” It’s almost a shame that Transatlanticism doesn’t end there. But, it wouldn’t be right to close Transatlanticism on any song that isn’t “A Lack Of Color.”

The closing track, “A Lack Of Color,” has a calming quality about it. However, “A Lack Of Color” ends Transatlanticism on a solemn note. The hushed ballad surveys Gibbard deceiving himself, “and when I see you, I really see you upside down,” and studies opposites: heart vs. brain, “fact not fiction,” before reaching a shattering ending. “A Lack Of Color” is mournfully honest. It’s an acoustic ballad done right. It’s short and not so sweet – thematically, anyway, and transitions all the way back to “The New Year,” with the rumbling, ascending train making its return. My heart falters when Gibbard chants, “I should have given you a reason to stay.” By the end of Transatlanticism, Ben Gibbard accepts that he’s alone. “A Lack Of Color” doesn’t tie up the album with a pretty red bow, and thank goodness for that. Transatlanticism saw Death Cab For Cutie undertake a brave, large sonic leap by sticking to their instincts, resulting in an album that’s equally expansive and personally affecting.

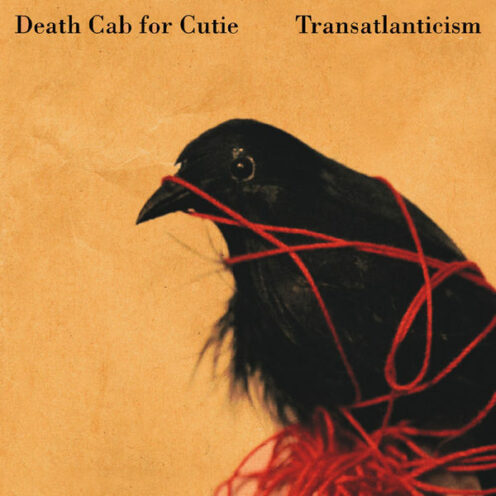

I first discovered Transatlanticism when I was 15 years old. Today, Transatlanticism turns fifteen. I can’t begin to explain how much I’ve grown and changed in the last seven years, but I can be assured that no matter what path I go down in my life, Transatlanticism will always provide an immense sense of comfort. It’s still my go-to album on a crisp autumn or winter’s day. Transatlanticism still invites nostalgia, motivates me to frequently remind my loved ones just how much I love them, and one day soon, the album art will be my first tattoo. It’s a journey, from the incoming train circling “The New Year,” making its way back to “A Lack Of Color.” The stories enclosed in this record are all stories we know, understand, but might not have articulated ourselves. As a result of that, Ben Gibbard comes across as an old friend. The instrumentation and production envelop listeners in warmth to this day. Death Cab For Cutie captured magic with Transatlanticism. Even now, its core concepts, transitions, fuzzy arrangements, and lofty ambitions are inspirational, to musicians and fans alike. Simplicity is beauty, less is more – I’ve always strongly believed in those statements, and that’s where Death Cab For Cutie find their biggest strength. Transatlanticism is supremely relatable, dramatic yet restrained, and its humble power will endure for many more years to come.