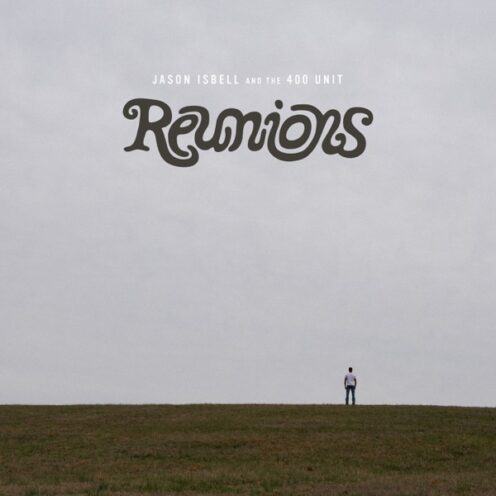

Jason Isbell is telling ghost stories.

Sometimes, the things that happen to us in our lives register immediately. Other times, years or decades have to pass for us to fully comprehend how a person or occurrence changed us. Time and experience lend perspective. They give us the wisdom necessary to look back and re-read the pages of our lives, reconvene with our former selves. That’s why reflection is so important, and it’s also why hearing one of our greatest living songwriters look back and commune with the ghosts of his past is so thrilling. Isbell has long been a master of craft: his songs have conveyed the struggles of addiction, the healing and humanizing powers of love, the joys of parenthood. But never before has he captured so thoroughly the bizarre and beguiling feeling of spending a moment inside a memory. On Reunions, by delving into his own past, this master songwriter finds new things to say about experience and identity, and about how the very act of living changes the stories we think are worth telling about our lives. It might just be his greatest album yet.

Isbell has gone on record to say that the songs on this album were things he wanted to write 15 years ago, but there were barriers in his way. “In those days, I hadn’t written enough songs to know how to do it yet,” he said. He hadn’t yet honed his songcraft into the razor-sharp knife it is now. He hadn’t gotten sober, which meant murky nights and hungover days with not enough energy left over to focus on the deeply personal layers he would need to excavate to tell these stories. Perhaps most of all, he hadn’t given himself enough time or distance to understand just how deeply the ghosts in these songs would prove to haunt him. It’s unnerving the way that regrets or papered-over traumas from our pasts tend to worm their way deeper and deeper into the recesses of our minds as years go by. Eventually, you end up alone with your thoughts on some solitary night, with nothing to do but dredge up those specters and let them speak. Reunions is the sonic equivalent of that kind of reckoning.

My dad left my family when I was a kid, before I was old enough to forge a real relationship with him. I never bore the brunt of his abandonment in the way my older siblings did, simply because I didn’t understand it. I didn’t understand what it meant to leave your family, the magnitude of his betrayal to my mom or to us, his kids. I didn’t realize that his decision to walk away—and subsequently, to not make any real effort to be a part of our lives—had already shaped the relationship I would have with him, fundamentally altering the course of my life in the process. That’s the way things go when you’re a kid, though: you suffer these wrenching heartbreaks and you don’t comprehend the full extent of them for years or even decades. I certainly didn’t. But there’s a song on Reunions called “Dreamsicle” that evokes recollections of my childhood that I didn’t even know I had. The lyrics are flickers of memory. They’re vivid as a photograph but move by rapidly like a film on fast-forward, because that’s how you remember things years after the fact. “Poison oak and poison ivy/Dirty jokes that blew right by me/Mama curling up beside me, crying to herself/Why can’t daddy just come home?/Forget whatever he did wrong/He’s in a hotel all alone and we need help.” There’s an innocence here that is profound and profoundly sad, because it’s all the things a child is too sweet and naïve to understand: the inappropriate jokes you didn’t get; the tears in your mother’s eyes from a sadness so soul-deep that you, used to crying over spilt milk and broken toys, could not possibly grasp; the belief that something as complex and full of grace as forgiveness could ever be simple. But then the chorus gives the answer for why that forgiveness is not in the cards: “New sneakers on the high school court/And you swore you’d be there/A heart breaking through the springtime/Breaking into June.” The father who didn’t show up when he said he would, or who left you alone when he shouldn’t have; the betrayals that felt small until they didn’t anymore; the tears you cried at 30 over something that happened when you were seven.

Nearly every song on Reunions elicits similarly deep and soulful meditations on the past. Take “Only Children,” an utterly haunting song where Isbell has a conversation with an old friend who has passed away. It’s a tale about the visceral way you can connect with someone when you discover you have something truly foundational in common. In this case, it’s music. These two friends “bet it all on a demo tape,” bond over Springsteen songs, and share their first clumsy stabs at songwriting with each other and no one else. “Will you read me what you wrote?” Isbell asks, before elaborating with the dismissal he gave his friend years ago: “The one I said you stole from Dylan.” Eventually, these friends lose touch, only coming back together again when one of them is in a coffin. “Heaven’s wasted on the dead/That’s what your mama said/And the hearse was idling in the parking lot/She said you thought the world of me and you were glad to see/They finally let me be an astronaut.” It’s an anguishing moment, full of unspoken regret about how silence can build up between two friends over time in such a way that it eventually becomes impossible to break. It’s fitting that the next bit of the song is the saddest guitar solo Isbell has ever played, because what do you say to a grieving mother telling you all things you always secretly hoped you’d hear someday from that long-lost old pal?

That’s the thing about ghosts: we talk to them because we can no longer speak to the people or things they represent. “Overseas” is a one-way conversation between a husband and a wife who have been separated by physical distance for so long that it’s built an emotional distance in its place. Isbell spends the chorus refrain singing about how their love “won’t change,” but he also knows it already has: “You’re never coming back to me/You’re never coming back at all.” Their love is the ghost, and the howling guitar solo at the climax of the song is its wail of anguish. “River” is a serial killer’s reverie, filled with the phantoms of the lives the character has taken. “St. Peter’s Autograph” is an examination of what it looks like to be supportive when your partner is wracked with grief you don’t share for a person you never knew. And “It Gets Easier” is Isbell’s discussion with the ghost that haunts him most: that of his former self. “It gets easier but it never gets easy,” he says of sobriety, speaking to the younger, drunken Isbell; “I can say it’s all worth it, but you won’t believe me.”

The last song on Reunions is called “Letting You Go,” and it’s the only song on the record that deals more with the future than with the past. It’s still filled with memory: most of the lyrics are recollections of the days after Isbell’s daughter was born, from driving her home from the hospital to sleeping by her side at night. But the weight of the song is in the final verse, where Isbell envisions the day, many years in the future, when he’ll walk his little girl down the aisle and give her away. And here, in this imagined moment, the idea of reuniting with old ghosts sounds a lot less frightening to him than what comes next. “I wish I could walk with them back through your life/To see every last minute of every last day/To hear your first words and to feel your first heartbreak/ To sing you to sleep when you’re scared of the dark/But the best I can do is to let myself trust/That you know who’ll be strong enough to carry your heart.” The song is obviously a rumination on fatherhood and on the deep, abiding love a parent feels for their child. But it’s also about time and legacy and mortality. After an album spent revisiting his ghosts, “Letting You Go” is where Isbell recognizes that, one day, he’ll be the ghost. His daughter will grow up and fall in love and build her own life, and the memories she’ll look back on will be as vivid and vital as the ones that have shaped him. His first impulse is to protect her: to shield her from the childhood pains that filled “Dreamsicle,” the pains that he himself—without meaning to—might inflict. Numerous times over the course of album, he imagines how his daughter would look at him if she were ashamed of him, and even amidst all the ghosts that haunt him, it’s clear that these thoughts are the ones that scare him to death. But just as children must learn to fight their own battles, parents must learn to relinquish their hold, and that’s what this song is ultimately about: “It’s easy to see that you’ll get where you’re going/The hard part is letting you go.”

Reunions is a heavy listen—weightier, in a way, than any other record Isbell has ever made. Isbell is no stranger to sad, haunting songs. This guy wrote “Elephant.” This guy wrote “If We Were Vampires.” But something about the songs on Reunions feels uniquely heartbreaking and unnerving, even in the Isbell oeuvre. Since I first heard this album, I haven’t been able to shake the bittersweet summer night recollections of “Dreamsicle,” the agonizingly regretful nostalgia of “Only Children,” the tranquil horror of “River,” the resilient defiance of “Be Afraid,” or the poignant emotion of “Letting You Go.” It doesn’t hurt that Dave Cobb’s production has never sounded lusher or more enveloping, or that The 400 Unit is playing with full sensitivity and might. But as with every Isbell record, it all comes back to the words, because no artist working right now cares so deeply about the language and stories that fill their songs. Reunions, more than any other album Isbell has written, feels like a work of literature, like a collection of short stories. It’s the rare album truly worthy of the word “masterpiece.”

Only Children

Only Children