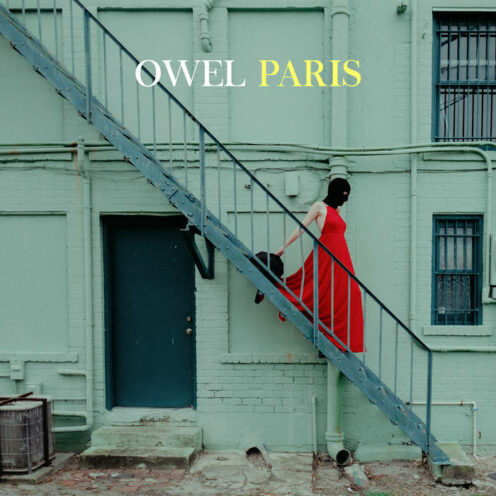

Back in February, on this very website, I predicted that Owel’s then-upcoming third album would be “just as vibrant, expansive, and gorgeous as its namesake” Paris. A single listen through reveals that to be true. Paris is a truly beautiful record, and, though it hasn’t even been out a week, it’s not inconceivable that it might be the band’s best yet.

Every Owel album feels like a cinematic experience, and Paris is no exception. Their last album, Dear Me, began the band’s slide towards the more symphonic end of the post-rock spectrum, and Paris pushes even further in that direction. There remains a heavy emphasis on crescendos and orchestral swells, but there seems to be less of a straightforward rock influence on Paris than there was on Dear Me. There are few moments like the catchy chorus of “Annabel” or the belted bridge of “I Am Not Yours” on Paris; instead, the climax of “A Message” is a whirlwind of strings and horns, and violin and piano take center stage on “Get Out Stay Out.” Jay Sakong is still a clear presence – thankfully, as he turns in perhaps his best vocal performance yet – but he doesn’t feel like the focal point of much of the record, giving every member of Owel equal weight.

What this means in effect is that the moments when the band really does let loose hit even harder. Every Owel album will be brimming with crescendos galore, of course, and it could get a little stale if every song ended with falsetto over a tremolo-picked guitar. The variation adds a little bit of welcome unpredictability to the album.

The album’s stunning finale “Goodnight” almost works like the album in microcosm, essentially a seven-minute crescendo that would make Godspeed You! Black Emperor proud. It’s a straight post-rock song in a way the band hasn’t attempted since the days of their self-titled debut, and it stands up to the best on that album easily. It’s the sparsest track on Paris, and maybe the most scattered in their catalog, consisting of only a guitar and piano or guitar and drums for most of the first half of its runtime. It makes the explosion at four minutes feel completely earned. That’s maybe the biggest thing with Owel; there’s a joke that writers should only use one exclamation mark throughout their career, otherwise they lose their effect. Owel is an argument against that. They’ve earned their every note.