Can it really be your “first documented, official pop album” if you’ve already released three of the biggest pop albums in recent memory? 10 years ago this weekend, Taylor Swift delivered the answer to that question, and the answer was a decisive, resounding “Yes.”

From the vantage point of 2024, it’s almost difficult to remember any version of Taylor Swift that wasn’t a world-conquering, stadium-tour-dominating pop star. The past two years of Taylormania have so thoroughly dwarfed any other pop star achievement in my lifetime that it’s even a little difficult to think back to pre-COVID times, when it seemed like the Taylor Swift machine was maybe starting to run out of gas. As mid-decade lists pour out from every music publication out there, I expect plenty of debates about what was the quote-unquote “best song” or “best album” of the decade. When it comes to discussing the artist of the decade so far, though, there is simply no debate: it’s Taylor, then it’s 93 million miles, and then it’s everyone else.

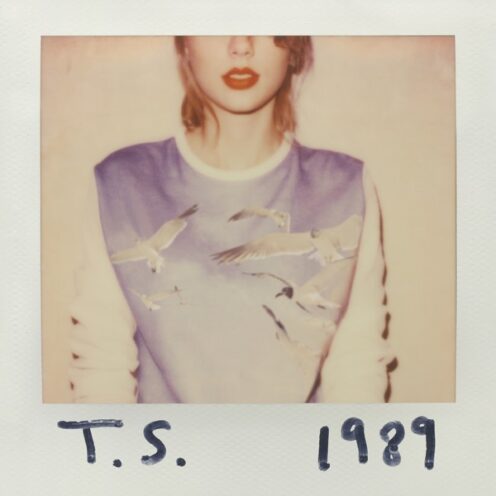

But it wasn’t always that way, and in the Taylor Swift story, it’s album number five, 2014’s 1989, that serves as arguably the most important inflection point between phase one Taylor and the force of nature we know today. Per the narrative, Taylor Swift before 2014 was a country star who had crossed over to pop music success but never fully left her Nashville roots behind. 1989, in being her “first documented, official pop album” – the weird phrasing she used to describe the LP when she officially announced it in August 2014 – was the album that made the crossover complete, and solidified Taylor’s status as the world’s biggest musical star in the process.

The thing with narratives is that they’re often predicated on half-truths. Real life is messy, full of all sorts of jagged edges and unclean lines. The stories we tell about our lives often sand away those edges to simplify the act of retelling. Such is also the case with artists and the stories they tell about their art, and it’s certainly true about Taylor Swift, someone who had absolutely made pop albums long before 2014.

Let’s review: Taylor arrives, at least as a recording artist, in 2006 with her self-titled LP. No arguments from me that this debut album is clearly a country record. The same is probably true about 2008’s Fearless, even though it achieved the kind of crossover that no country album in my lifetime up to that point had achieved. There had been massive, massive country acts in the ‘90s, of course: Garth Brooks and Billy Ray Cyrus and Shania Twain and Faith Hill and the Dixie Chicks. All those artists sold tons of albums, and most of them scored massive hits. Faith Hill even had the top-charting song of 1999, besting Santana and Rob Thomas and “Smooth.” With Fearless, though, Taylor felt more embraced by the pop mainstream than any of country’s ‘90s titans, especially as songs like “You Belong with Me” and “Love Story” broke down every genre barrier out there. Fearless was also an awards show darling in extremely notable ways, whether Taylor was beating out Beyonce at the MTV Video Music Awards (much to the chagrin of a certain rapper) or winning her first of four (and counting) Album of the Year Grammys.

So, that’s one true-blue country album, and one album that rode the pop-country divide so cleverly that it brokered a new kind of peace between pop listeners and country listeners. The widespread embrace of Fearless set the stage for two albums that arguably have more pop in their DNA than country.

2010’s Speak Now throws Nashville a couple bones, in the form of songs like “Mean,” “Back to December,” and the b-side “Ours.” But it’s also got pure pop moments like “The Story of Us” and “Sparks Fly,” and big rock songs like “Haunted” and “Better Than Revenge.” It was also the first Taylor album to sell a million copies in a week, a mark previously only achieved by one country album: Garth Brooks’ Double Live from 1998.

2012’s Red is even more blatantly “not country,” and that’s even leaving aside the trio of Max Martin productions. When the gestures on that album aren’t leaning aggressively pop – see the glitchy chorus hook production on the title track, or the work of producer Jeff Bhasker (by then famous for his work with Kanye West and fun.) on “Holy Ground” – they lean arena rock, like on the U2-inspired “State of Grace,” or the Snow Patrol collaboration on “The Last Time.” If you squint, I suppose “All Too Well” is a country song, and maybe “I Almost Do” or “Begin Again,” but it’s clear on Red that Taylor was almost all the way out of Nashville’s door.

And yet, 1989 remains known to this day as Taylor Swift’s first big pop play. 10 years after the fact, the narrative that Taylor set with a six-word phrase – “my first official, documented pop album” is still intact. It’s proof that, for as good as she is at writing songs, she’s maybe even better at marketing herself and her music to the world.

Listen back to 1989 and it’s not really any more or less pop than Red. The production gets bigger, glossier, bolder, and more in your face on the big singles – “Shake It Off,” “Blank Space,” “Style,” and “Bad Blood” – but there are still the in-between songs. “Wildest Dreams,” “How You Get the Girl,” and especially “This Love” gesture back toward country, and stuff like “I Wish You Would” and “I know Places” points toward Taylor’s rock music side – the former a more indie-centric, Haim-esque version, the latter the same Paramore-style pop-punk music she was flirting with on Speak Now. I get the sense that a lot of people remember 1989 primarily for its first half, which is where most of those huge singles live. But a listen back shows that it’s not all technicolor ‘80s synths – and as such, that it wasn’t as big of a departure as most of us made it out to be back then.

Not that it mattered. Taylor officially declaring a pop move on 1989 gave a lot of listeners permission to fall in love with her music. I remember when I climbed aboard the Swiftie bandwagon in the leadup to Speak Now, there was still some stigma online and in my social circles about seriously listening to her music. A lot of people were still writing her off as teenybopper trash. Speak Now moved the needle a little bit, and Red moved it more, but there were still obstacles – namely, the “country” genre tag, a huge issue for the (very large) crowd of people out there who insisted they “like any music other than country.” (This crowd is still massive, even to this day.) So what that Red was more arena rock than country? And so what that its credits were stacked with more rock and pop collaborators than country names? The genre tag simply mattered. Taylor Swift knew it, which is why she let it go on 1989 and never looked back.

I could probably count on one hand the number of albums that I’ve anticipated with more furor than 1989, and they’d probably be obvious to anyone who has ever interacted with me online. Butch Walker’s The Rise and Fall of Butch Walker and the Let’s-Go-Out-Tonites!; Jimmy Eat World’s Chase This Light; Jack’s Mannequin’s The Glass Passenger; Green Day’s 21st Century Breakdown; The Dangerous Summer’s War Paint. Those five albums were all follow-ups to records that reshaped my music taste and shook me to my core. The thought of hearing whatever came next, in each case, kept me up at night and had me counting down the days for when those albums came out.

1989 was THAT kind of album. Red had meant so much to me during my last year of college – and had lingered so profoundly in my bloodstream for the ensuing two years – that I simply could not wait to hear where Taylor Swift would go next. But I also felt some apprehension about the album, for the same reason that a lot of people were excited for it. The pivot to pop opened up the Taylor Swift tent and made it bigger than ever before, but I was worried going that route would require Taylor to strip away some of the detail and honesty of her lyrics in favor of songwriting that would fit more comfortably into a radio-pop package.

I needn’t have worried. The thing about country music is that it prizes economy of language and storytelling above all. Nashville songwriters hammer away at their tunes as if they were blacksmiths, until the songs are as sharp and well-honed as possible. You don’t use a seven-word phrase in a country song when a five-word phrase would do. Taylor learned that from the best in her early days – particularly, collaborators like Liz Rose and Nathan Chapman – and it served her well when she linked up with Max Martin and got acquainted with his “melodic math” philosophy of songwriting. It turned out that Taylor was already writing mathematically perfect melodic phrases in her music – think lines like “You made a rebel of a careless man’s careful daughter,” or the entire refrigerator light section of “All Too Well.” And so, when it came time to write 1989 staples like “Blank Space” or “Style,” Taylor already had all the tools to deliver exceptionally addictive pop songs without losing her narrative spark in the process. The first time I heard her utter the line “Darling I’m a nightmare dressed like a daydream,” I knew my fears for this album had been unfounded.

That’s ultimately the brilliance of 1989: The songs can sound simple and fluffy and lightweight on first or second listen, but they’re not your average pop songs. Taylor’s version of going pop wasn’t turning in her Teenage Dream, in other words – an album rich in melody and attitude but mostly bankrupt in ideas or emotional gravity. It may have a song called “Style,” but 1989 is not a style-over-substance exercise. Instead, 1989 is an incisive critique of fame and its costs. On “Blank Space,” Taylor gleefully satirizes and skewers her own tabloid image, while songs like “I Know Places” and “Out of the Woods” stand as darker examinations of being the girl no one will ever leave the fuck alone. Once the album winds around to cuts like “This Love” and “Clean,” you sense that Taylor might be verging on a breakdown – frustrated at the end of another broken relationship, wondering if she’ll be lonely forever, ready to start blaming herself and her own stupid fame for making love so goddamn hard.

18 years in, the central tension in the Taylor Swift discography might be the push and pull between her love songs – wildly vulnerable, openhearted things that portray a person ready to leap off the high dive if it means finding happiness with the right person – and the difficulty of making those love stories last when you are, literally, the most famous person on planet Earth. “Would it be enough if I could never give you peace?” Taylor would ask on an album released six years after this one, in the midst of the relationship that seemed like it might be her happily ever after. 1989 was the first time she hit upon some version of that question, and I remember it being the idea that fascinated me most as I dove into the album during the weekend after its release. While most other critics were fawning over the sheer euphoric explosion of these songs – the big melodies, the bigger production – I came away wondering whether 1989 might be the saddest Taylor Swift album.

“Clean,” the album’s magnificent closer, certainly supports that argument. Up to this point, Taylor had always ended albums with uplift: The “play it again” enthusiasm of “Our Song” on self-titled; the fight song vibes of “Change” on Fearless; the way “Long Live” ended Speak Now with a victory lap, recontextualizing Taylor’s Grammy victories like they were fairytale triumphs on the level of slaying dragons; and, on Red, the love story starting anew with “Begin Again.” “Clean” was stark in comparison, a song from a girl who’s sworn off love like it’s a bad drug, but still remembers all the feelings the way the fabric on a wine-stained dress remembers the spill. “Instead of paying tribute to her band or basking in the rays of a new love, she’s weathered and world-weary here, steeling herself for another battle while all the while knowing that she’s lost something precious in the war,” I said of “Clean” in my original 1989 review. “And as this album proves time and time again, she wants that something back…even if she has to fight against her own fame to find it.”

In that way, 1989 has to be considered the definitive Taylor Swift album. It is not, in my mind, the best one. But by setting her heartbreaks and insecurities and dissatisfactions to songs that often sound like a stadium-sized dance party, Taylor took the diaristic relatability of her earlier work and paired it with something every pop listener could bop along with. I think that’s probably why 1989 still out-streams other Taylor Swift albums, why that section of the Eras Tour drew perhaps the biggest response from the crowd, and why last year’s 1989 (Taylor’s Version) is – so far – the only one of the re-recordings to move more than a million units in its first week. The album works not because it’s just pain or just euphoria, but because it’s the album in Taylor’s discography that melds those two things most effectively.

It works, you might say, because it’s a nightmare, dressed like a daydream.