Artform will never cease being a self-involved & possessive medium for any and all onlookers. One can’t help but draw their own experiences in order to relate to whatever it is they see or hear from any artist, whether it be a painter, musician or filmmaker. Part of including our own relation to a piece is referring to our historical worldview, always spotting influence & inspiration. A song lyric, a brush stroke or even part of a character’s outift — we’re bound to pick out what we recognize, making it easier as participants to relate to the artist’s motivation and our own perspective.

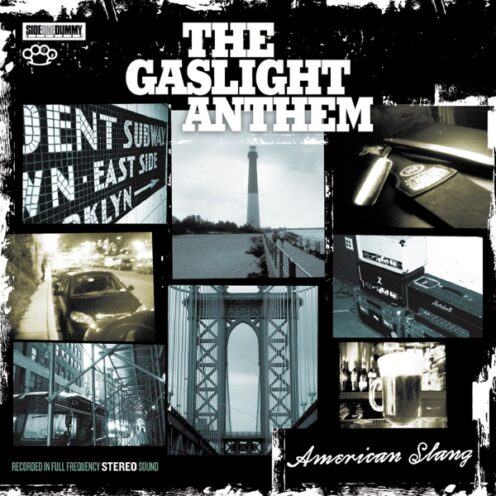

In five short years, New Jersey quartet The Gaslight Anthem have gone from punk rock bruisers to one of the most celebrated & prolific modern rock acts on the scene. Much of that success stems from the band’s ability to seamlessly weave influences into their music, both in terms of lyrical reference and overall sound. With their 2008 breakthrough, The ’59 Sound, music fans relished the opportunity to hear a large combination of influence from Bruce Springsteen and Elvis Presley, something that was heard not only through the raspy vocal charm of Brian Fallon, but also through a more traditional, old-school production (courtesy of Ted Hutt, who is also present on this record). Many of the themes and style were reminescent of 1950’s rock n’ roll, something the band used to their advantage. With their third full-length, American Slang, the distinction between individual art and influence continues to grow, offering everyone on board a chance to carefully sift through and pay tribute to the influential legends, all while concocting their own sound for the future.

Perhaps it is more appropriate to think of the record as a historically-accurate gateway; a 35 minute History of American Rock & Roll course on compact disc, if you will. American Slang takes the best of what the band has shown they can do, and moves it into early ’60’s Motown, combining it with a rich Springsteen/Strummer sound (which is just how Fallon will always be; it works for him, get over it) over a soulful rhythm section, with sprinkles of Sam Cooke, Otis Redding and Smokey Robinson in there for good measure. The title track nestles itself in comfortably as a more adept & homogenized version of Green Day’s “21st Century Breakdown,” with fewer direct references to recognizable icons, and simply calling all we know & love about the golden age of FM radio, the cultural language of our nation (or “American Slang”).

”Stay Lucky” is a pop gem, a sparkling rhythm taking over a cascading and flowing melody that never leaves the song’s soul, and leads it into a track that is like the Rolling Stones at their peak. “Bring It On” might riff a bit on early Beatles (“Please Mr. Postman”), but it’s got a brilliant Jagger-like feel from Fallon, who is a splendid vocalist — and someone who truly worships these icons, but never feels like he’s plagiarizing — but he leaves a lot of space for the other members to leave an impression. Benny Horowitz delivers a whiz-bang approach to the drums, all while staying classy and giving the light production touches some serious lift. Hutt doesn’t allow the mix to get in the way of each song (as was a minor complaint from some regarding the previous disc), instead zeroing in on the vocal strengths of Fallon and a lo-fi, but room-filling aura from the others in the band. “The Diamond Church Street Choir” finds Fallon having some of his most soulful experiences in the last moments of the tune, but the rest of the band turns in a winning set, inspired by the greats, such as Redding and the Spinners, Motown musicians who kept it honest and played beautiful instruments.

There is still a story buried within the context of this album. You’ll hear mentions of the Queen, the Cool, and others from time to time. The burroughs of New York and even London are brought up, perhaps as a hint of where future records will begin to go (the British Invasion and the punk scene were on the verge of blowing up in the late ’60’s). However, there is no single narrative lurking beneath this record. It has a story to tell, don’t let anyone fool you, but the album is more of a celebration; a celebration of post-war America finding its most potent identity thrust into a turbulant era of culture & politics clashing between one another. “Well they say these days, nothing comes cheap and everything has a price. Everything has a price, nothing is free; not even me,” Fallon sings on “The Queen of Lower Chelsea.” Fallon relates to and hints at these timeless struggles, what the power a single melody can have on one person. In the bittersweet anthem “Orphans,” lyrics read “I have given you the blood and the truth, from the wounds that they laid on me, and whatever they left, I kept it for my own heart.” Call it melodramatic if you must, but that’s some kickass Americana-type poetry that even Ginsberg would want to high five.

”Boxer” is both punk and rock n’ roll clatter, driven by an alleyway-tin can beat with the idea that words & ideas, even of others, heal more wounds than anything worth the initial fight (“He took it all gracefully on the chin, knowing that the beatings had to someday end. He found the bandages inside the pen, and the stitches on the radio”). Both “Old Haunts” and “The Spirit of Jazz” continue to compliment the idea of music as the ally, a cliche if you’ve ever heard one, but one that truly gets a revitalized injection of adrenaline from how Fallon tells you to use it; how “the good times are gone and you should let them go,” that the youthful anthems you sang to yourself will no longer remain as true once you learn what the world can do to you, and everything in it. Pessimistic by album’s end? Sure, if you want to see it that way. As the times showed us, the decade of soul occasionally lost its way, and as an American narrative, told from the heart of it all, Fallon’s words contain a great sense of progression and very little regret. It is a sentiment that was maintained through even the most difficult points for many citizens during the decade, who relied on the radio to be their sole fixture through heartbreak and remorse.

As the album closes on a song that ducks out before any genuine build-up, it’s clear that for as many times cliches & well-worn philosophies are hinted at, the band is not up for predictability. The closing song is about as far away from “The Backseat” as one can get, yet historically, as the 1950’s came to a close, America was opened up to a series of unforeseen events that would alter the face of a world still rebuilding from the post-war era. The Tom Waits-esque growls that peek around in the background of “We Did It When We Were Young” are not as foreboding as Fallon makes them appear, however. From the beginning of the album, Fallon lets you know that America (and it’s music) has taught him everything — but “I am older now,” and adapting to lost youth is the most important (and difficult) aspect of growing up, particularly during a new time when nothing is ever certain. If there’s anything the Gaslight Anthem are able to teach us, it’s that transitions might appear bumpy, but as the present becomes the past, the road evens out as appropriately as you would intend it to.

Bring it On

Bring it On