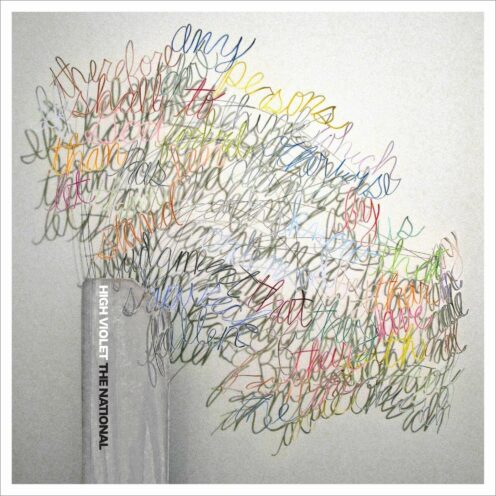

When The National reemerged in 2010, they were primed to explode. It didn’t matter that they were coming up on their fifth album and had already passed the milestone that marked their first decade together as a band. They were, as people have often described their albums, a slow burn, or a grower, and by the time the new decade began, their fuse was ready to blow. 2007’s Boxer had changed the game for the Cincinnati fourpiece in more ways than one, turning them into prestige indie darlings, landing songs on the soundtracks of virtually every moody drama on television, and even earning them a small but memorable role in the campaign of a presidential hopeful named Barack Obama. By the time The National appeared on Jimmy Fallon in March of 2010 to officially kick off the rollout for High Violet, with a majestic performance of “Terrible Love,” it was clear they were ready to be rock stars.

Even before this record, The National had proven their ability to make a big noise. Songs like “Abel” and “Mr. November,” from their 2005 LP Alligator, both explode into vicious crescendos. Even the quieter, more measured Boxer had served up the kinetic “Mistaken for Strangers.” But High Violet was something new. “Terrible Love” gave fans the first taste of what the record might sound like, but it was “Bloodbuzz Ohio,” released for free download on the band’s website in April of 2010, that served as the proper first single. Together, these two songs offered a vision of a new kind of National: one with a U2-style scope and a gift for yearning, bittersweet crescendos that could scrape the cheap seats. I remember reading at least a few dismissive comments on the two songs from early National fans, who felt the band was selling away what made them special to chase “that Coldplay money.” That comparison isn’t quite accurate, but it’s also not entirely wrong: on High Violet, The National briefly found a way to pair their murky, mopey, intellectual societal commentary with songs that sounded as big and polished as anything being made by the biggest rock bands of the time. In that sense, you might say that it was their Automatic for the People.

Ever since High Violet, there’s been this sort of push and pull for The National—between embracing their ability to be a big, universal rock band and following their desires to be a little weirder, a little quirkier, a little more introverted, and a little bit left of the dial. That tension is what drives this album. It’s why the record opens with something as grandiose as “Terrible Love,” but also why the band opted for the scuzzy demo version rather than the pristine (and superior) full studio version. It’s why “Runaway” and “England,” two of the loveliest ballads in the entire National discography, are bisected by “Conversation 16,” a song about a marriage crashing onto the rocks where the key line is the alarming “I was afraid I’d eat your brains.” It’s why even the songs that seem like they would be devastatingly sad include lines that seem to be there just to make you crack a smile (“Sorrow’s a girl inside my cake,” frontman Matt Berninger sings on the song “Sorrow,” which is, bizarrely, one of the happiest songs on the album).

Then again, The National never lacked a sense of humor. Once, the band played the aforementioned “Sorrow” for six hours straight as part of an abstract art experiment. The concert was released as a nine-LP set called A Lot of Sorrow (a legitimately hilarious title) which Pitchfork honored with a 7.2. On High Violet, that humor exists beside sadness, regret, longing, nostalgia, existential dread, and ultimately, the reverie and freedom of young adulthood. If you’ve ever been sad at a bar at 2 a.m., wondering where your life was going but still willing to make self-deprecating jokes to your friends, then High Violet probably appeals to you. There’s an aimlessness to the characters and stories on this record that only a bit of wry humor can temper. The touches of that winking self-awareness are ultimately what make the tales of High Violet feel so vivid and real. Even as he’s singing the songs, Berninger seems to be trying to play it off like he maybe doesn’t mean the words that are coming out of his mouth. Who hasn’t been there? Whether you’re a twentysomething trying to fit yourself into the rubric of “adulthood” or a thirtysomething trying to get used to the new wonders and terrors of parenthood, these songs resonate.

“Terrible Love” presents us with a protagonist who is “walking with spiders,” which brings to mind images of fantastical tales, or of nightmares. In reality, though, High Violet is mostly interested in spitting us through all the anxieties and worries of day-to-day life. The characters in these songs, ultimately, are not fantasy heroes contending with the ferocious giant spiders of Tolkien. Rather, they’re everymen: they’re knowable; they’re normal; they’re mundane. And they’re suffering crushing defeats. “Anyone’s Ghost” is about the emotional distance that builds up between a couple who run out of things to say to one another. “Afraid of Everyone” is about the technicolor terror you feel when you bring a child into the world and suddenly realize just how many things could jeopardize that precious, innocent, vulnerable life. “Conversation 16” is about a husband and wife still trying to playact the charade of a happy, loving marriage—even as their unwillingness to accept the truth of their disintegrated bond begins to corrode their very souls. Berninger’s lyrics repeatedly capture evocative, cinematic images—wandering through “the Manhattan valleys of the dead” on “Anyone’s Ghost,” or escaping to the utopian “Lemonworld” in the song of the same name—but most of High Violet is grounded in the domestic. It’s quiet houses and grayscale office spaces, sputtering relationships and dead-end jobs. When Berninger’s walking with spiders in “Terrible Love,” he’s probably just walking with his own fears, his own regrets, his own inadequacies. The rest of the album continues that journey.

Sitting right at the midpoint of High Violet is “Bloodbuzz Ohio,” and it’s a fitting reverie—an eye at the center of the album’s storm that offers a small but significant reprieve from the darkness. Here, rather than singing about the troubles of his present, Berninger reflects on his past, getting drunk on the memories he has of his old home state in the way you might get tipsy on half a bottle of red wine. “I never thought about love when I thought about home,” he sings in the chorus. You could interpret that line in multiple ways, but I always heard it as a realization, later in life, that you took home for granted. When I first heard “Bloodbuzz”—late in my freshman year of college, when I’d spent more time away from home than at any other point in my life—that line hit me like a knife to the heart. In the song, it’s easy to take the lyric at face value: as Berninger’s proclamation that he doesn’t think much of his old hometown in Ohio. But the mood of the song—warm, enveloping, wine-buzzed, and lit like a noir photograph—says something else. Home lives in your blood, and when you leave it, it comes back to you at unexpected moments, accompanied by unanticipated pangs of longing.

That “Bloodbuzz Ohio” lands in the middle of High Violet seems like no accident. So much of this album is about the dissatisfaction of early adulthood. And what do most of us do when we hit that kind of post-college malaise? We look back: at youth, at home, at old friends, at innocence; at a time in our lives that, maybe, was a little less burdened by bills or lies or heartbreak or anxiety. 10 years ago, I loved that song for what it seemed to suggest: that going home might be as simple as falling into a trance-like dream and being carried away by a swarm of bees. Today, I might love it even more, if only because I’ve come to understand the other songs on High Violet a little better. Some albums click right away. Others require more from you: your time, your experiences, your losses, your defeats. I loved High Violet then; I’ve lived it now.

Sorrow

Sorrow