When the world got blown apart on the morning of September 11th, 2001, it felt like nothing would ever be the same again. In a lot of ways, it wouldn’t. Even at 10 years old, I knew there was a sense of innocence and wonder to the world that was stolen the moment that first plane hit the North Tower of the World Trade Center. How could anything ever be okay again after something so terrible? Even as a child, I pondered this question.

For years after that day, I would read about the reactions to the tragedy. Shortly after I graduated from high school in 2009, I read a speech that Dr. Karl Paulnack of The Boston Conservatory gave to the parents of incoming students in September 2004. In the address, Paulnack reflected on his experience on the morning of September 12th, 2001, when he—a classical pianist by trade—went to sit down at his instrument to practice. It was part of his daily routine, but on that day, it felt wrong. “Playing the piano right now, given what happened in this city yesterday, seems silly, absurd, irreverent, pointless,” Paulnack recalled. “What place has a musician in this moment in time?”

But then, as Paulnack describes, he “went through the journey of getting through that week.” As the career musician shunned his piano and debated whether or not he would ever feel inspired to play again, he observed how the people of New York picked up the pieces of their lives:

At least in my neighborhood, we didn’t shoot hoops or play Scrabble. We didn’t play cards to pass the time. We didn’t watch TV. We didn’t shop. We most certainly did not go to the mall. The first organized activity that I saw in New York, on the very evening of September 11th, was singing. People sang. People sang around fire houses. People sang “We Shall Overcome”. Lots of people sang America the Beautiful. The first organized public event that I remember was the Brahms Requiem, later that week, at Lincoln Center, with the New York Philharmonic. The first organized public expression of grief, our first communal response to that historic event, was a concert. That was the beginning of a sense that life might go on. The U.S. Military secured the airspace, but recovery was led by the arts, and by music in particular, that very night.

Paulnack’s reason for recounting these stories as part of a welcome address was to ensure parents that their children were making a noble career choice: that devoting one’s life to music couldn’t be a mistake when music is what saves us when nothing else can. Certainly, his words and the sentiment behind the rest of his speech—which you can and should read here—resonated with me as I prepared to major in music myself. But the stories he told—about how music helped our nation pick itself up again after 9/11—were things I’d already seen firsthand, seven years earlier.

When the World Trade Center towers collapsed in the fall of 2001, I hadn’t yet reached my musical epiphany. It would be another two years before I started buying albums and another three before I became an obsessive listener. But I was still rooted to my couch on the evening of February 3rd, 2002, when an Irish rock band took the stage and showed me and the rest of America how music could heal. That night was historic for several reasons, not least because it brought Tom Brady and the New England Patriots their first Super Bowl victory. (Early last month, 15 years after the fact, they clinched their fifth.) However, as someone who did not (and really, does not) care about football, I was more interested in what was going on at halftime. I knew U2 only vaguely at the time, through the pair of singles from their All That You Can’t Leave Behind album (“Beautiful Day” and “Stuck in a Moment”) that I’d been hearing on the radio since the previous summer. Still, I knew I liked those songs enough to at least pay attention to the halftime show.

When the big banner started rising behind Bono and the band as they played the prayerful “MLK,” I didn’t immediately register what was going on. Watching the show back, when the banner first appears, it just says “September 11th 2001” with “American Airlines Flight 11” in smaller type below. But then the names appeared and I realized what they meant. I realized who those people were and the fact that U2 was essentially turning their big Super Bowl moment into a memorial service for everyone who lost their lives on that fateful day the previous fall. When the first notes of “Where the Streets Have No Name” echoed through the stadium, chills shot down my spine. And at the end of the song, when Bono ripped open his jacket to reveal an American flag sewn on the inside, I felt adrenaline coursing through my entire body. It didn’t matter that I didn’t know the band very well, or that I didn’t know the song. I knew enough to know that the moment would forever be iconic.

15 years later, I still get tears in my eyes whenever I hear the Edge’s guitar riff for the first time near the beginning of “Where the Streets Have No Name.” When I saw U2 live in 2011 and heard that song echo around a stadium on a gorgeous summer night, it was life-affirming. And even today, I’m still comparing every other Super Bowl halftime show to the standard U2 set in 2002. The combination of moment, song, and grand gesture renders the show one that cannot and will not ever be topped—not even by Prince playing “Purple Rain” in the rain or Springsteen doing an exuberant crotch slide into the camera. It seems almost bizarre looking back, that the most powerful musical reaction to 9/11 came from a band made up of four Irish guys. But that fact is arguably what made the show so powerful: if an American rips open his jacket to show off the stars and stripes sewn inside, there’s almost no way it doesn’t come across as corny or pandering. When Bono did it, it sent a grander message: not “We Are One Nation” but “We Are One World.”

Then again, U2 have long done a better job of being a great American band than virtually any actual American band. Their first few records—specifically 1980’s Boy and 1983’s War—sound distinctly European, carrying a post-punk sound with more than a little bit of German danger and British swagger in it. But with The Joshua Tree in 1987, U2 wanted to examine the roots of rock ‘n’ roll music—a pathway that led them to America.

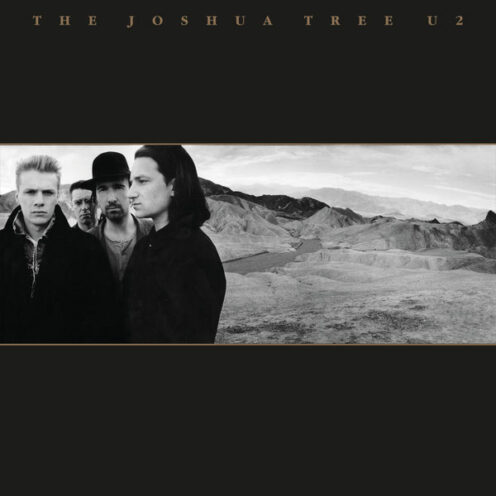

So much of The Joshua Tree is American, both in vision and sound. The photographs on the sleeve and in the liner notes found the band out in the deserts of Joshua Tree National Park. When the album was written and recorded, the members of U2 were also reading the works of American writers and engaging with American politics. The resulting album paired American musical forms (the blues, early rock ‘n’ roll influences, plenty of American folk, and even a bit of country) with U2’s growing penchant for arena rock, which had already been coming to the forefront on the band’s previous album, The Unforgettable Fire. It also paired the idea of America as a promised land with the disenfranchisement of the Reagan era. Add in the spirit of discovery that the band members felt in embracing American culture for the first time and you have the blueprint for The Joshua Tree.

Every once in a while, bands make quantum leaps between records. They go from being promising musical outfits to making all-time-great albums in a matter of just a few years. On the list of rock music’s greatest quantum leaps, The Joshua Tree has to be near the top. The Unforgettable Fire was a solid, hit-or-miss record. The best songs—material like “Bad” and “Pride (In the Name of Love)”—reach for the heavens with chilling earnestness. Tunes like “Elvis Presley and America,” though, are depressingly half-formed, keeping Fire from being a truly great record.

From the opening moments of “Where the Streets Have No Name,” it’s clear that The Joshua Tree was the sound of U2 finally making good on all their potential. The record is understandably most famous for its first three tracks—all of which are among the best songs ever written. “Streets” is (with apologies to “One”) the band’s finest hour, with a propulsive rhythm and a rafter-raising chorus that combine to make it one of the all-time great running songs. (There’s a reason it was featured in the trailer for a Steve Prefontaine movie back in the day.) “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” meanwhile, is an aching paean to spiritual yearning, while “With or Without You” sees Bono trying to reconcile his life as a touring musician with his responsibilities as a husband.

You’d be forgiven for feeling like The Joshua Tree was three great singles at the top and then a bunch of songs that weren’t as good. Early on in my U2 fandom, I struggled to get into the latter parts of the record, particularly side two. I preferred the cleaner, more modern All That You Can’t Leave Behind, a record whose triumphs are more evenly scattered throughout its running time. I later read that the person who did the sequencing for The Joshua Tree—a band member’s girlfriend, I believe—put the songs in order based on how much she liked each of them. If that’s really the case, it makes sense that the record is top heavy.

But the latter segments of The Joshua Tree, while not offering the same immediacy or universality of those first three tracks, contribute the majority of the record’s thematic heft. “Bullet the Blue Sky” is a scathing anti-war song and a loud, angry indictment of the United States’ imperialistic foreign policies. The song was originally written about America’s involvement in the Salvadorian Civil War, a conflict where the United States fed the flames of violence in El Salvador and then turned around and denied asylum to most of the refugees who were fleeing the war-torn country. 30 years later, “Bullet the Blue Sky” remains troubling and prescient. We’re living the same shit in a different decade—part of the reason U2 have decided to take The Joshua Tree on the road again for the 30th anniversary of its release.

The rest of the record is just as heavy. The folk-influenced “Running to Stand Still” humanizes the horrors of heroin addiction; “Red Hill Mining Town” is about the 1984 miner’s strike in England; “One Tree Hill” is an ode to a late friend that Bono spent time with in New Zealand while on the Unforgettable Fire tour; “Exit” enters the troubled mind of a serial killer; and “Mothers of the Disappeared” returns to El Salvador, shining a light on the mothers of children who were kidnapped in the night and never seen again. Like “Bullet the Blue Sky,” “Mothers” serves as a rebuke of U.S. foreign policy, taking our government to task for assisting in regime changes and backing new governments that are just as bad as the old ones.

U2 are often regarded as a band whose songs are big, anthemic, and inspirational—hence their status as arguably the greatest stadium rock band of all time. But while the songs on The Joshua Tree are big and blood-pumping, the record is far darker and more complex than what first meets the eye. This trend has continued throughout the band’s career. Bono has never carried the same level of skill with narrative and character writing as fellow legends like Dylan and Springsteen. His talent is parlaying both personal and political subjects into lyrics that are simple and abstract enough to be relatable to millions of people. Even if you’ve never faced down the darkness of unemployment with bills to pay and a family to support, you can shout along with the “Love, slowly stripped away/Love has seen its better day” bridge of “Red Hill Mining Town” and see what you want in those words. Often, U2’s songs are clever Rorschach tests that fold deeper layers of nuance into their face value charms.

That clever balance in the songwriting on The Joshua Tree—between specificity and universality—has also allowed the songs to grow and change with the times. When Bono wrote “Where the Streets Have No Name,” he was responding to the suggestion that, in Belfast, Ireland, you could tell a person’s class, religion, and politics by asking the name of the street where they lived. The idea of going to a place “where the streets have no name” was to find a utopia where those divisions faded away and everyone came together. In 1987, Bono said he thought that a great rock concert could be that place for people. I always took the song to be about heaven, or the afterlife in general. In any case, after the towers came down on September 11th, it was easy for the song to become a call to action for that moment—a reminder to stay united when the impulse was to divide.

In 2017, the messages behind “Streets” and every other song on this album feel as apt as they ever have. At least in the United States, we feel more divided—by politics, by race, by gender, by sexual orientation, and by our own differences in opinion—than I remember us feeling at any prior point in my lifetime. Amidst this tension and strife, it feels almost serendipitous that a record like The Joshua Tree is marking a three-decade milestone. On the one hand, it’s sobering to know how little we’ve moved forward in the past 30 years. Why do we still let bitter, violent division take root? Why do we still stand for a government that wages undeclared wars and props up foreign administrations that commit horrific atrocities? Why do we still let the failed “War on Drugs” stigmatize people like the heroin-ravaged couple in “Running to Stand Still”? Why do we fail, at every turn, to show compassion? Why the fuck don’t we ever learn anything from history?

On the other hand, though, it’s comforting to know that U2 will be back on the road this year, bringing these songs back into the limelight and giving another generation a chance to unfurl their meanings and lessons. Looking back on The Joshua Tree 30 years later, U2’s fifth record and magnum opus still seems undeniably timeless. That fact alone is something to celebrate, and it’s why I write these retrospective columns in the first place: to look at how the best music can still hold weight and meaning even so many years after it was written. But my greatest hope is that in another 30 years, these songs and the messages behind them will be seen as out-of-date. As relics of a time when we weren’t so enlightened. As reminders of the problems that we used to have. Because if this album isn’t timeless 60 years after the fact, then maybe we will have made some goddamn progress.