“I’m not happy with myself these days, I took the best parts of the script and I made them all cliche/And this red bandana’s surely gonna fade, even though it’s the only thing the fire didn’t take.”

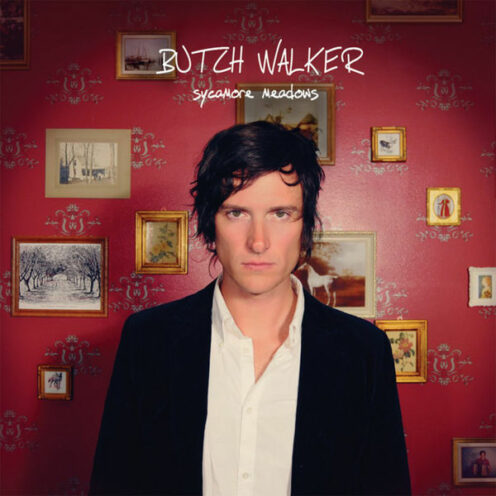

Butch Walker sings those lines on “Going Back/Going Home,” one of the standout tracks from his fourth solo studio album, 2008’s Sycamore Meadows. That’s not a metaphorical fire, either. In November 2007, Walker lost his Malibu home, along with every guitar he’d ever owned and every master tape of every song he’d ever recorded, in a vicious assault of California wildfires. Pieces of recording equipment, cars, motorcycles, family heirlooms, photographs from happier times—they all turned to ashes on November 24 of that year. Luckily, Butch and his family were on tour in New York and no one was hurt, but the songwriter was suddenly cut adrift from all material possessions, forced to start over. The L.A. party of his previous record, 2006’s The Rise and Fall of Butch Walker and the Let’s-Go-Out-Tonites!, was more than over: it was a distant memory, a piece of another life. In his first public statement following the fire, Butch said “I feel like I finally know the difference between ‘going back’ and ‘going home.’” It wouldn’t be long before he would channel that sentiment into a song and album that were arguably career-defining moments for him.

The way Butch tells it in his 2011 memoir, Drinking with Strangers, the fire came along and shook him awake. Throughout the fall of 2007, the artist had been taking advantage of social media (remember Myspace?) to disseminate some of his latest demos to fans. Boy, was this new stuff sounding great. I remember coming home from school on the first or second day of my junior year of high school and logging into my email or Facebook or some other source that told me Butch had posted a new song. When I started listening, I was blown away: this particular tune was a slow, somber, and emotional piano ballad that I immediately thought was one of the best songs he had ever written. The power in his voice, the sparse arrangement, it reminded me of the first time I had heard Letters, and I couldn’t wait to see what Butch Walker had in store for his new record. That song was “ATL,” which would become the closing track on Sycamore Meadows a year later when the album finally made it to official release. And it wasn’t the only song that Butch premiered to fans online that fall. One day, the after-school discovery was a chiming ode to two lovers losing their connection; another week, it was a raucous rock ‘n’ roll track played on a 12-string guitar; and a fourth song sounded like it had potential to be Butch’s next big shot at mainstream radio. Those songs, “Vessels,” “3 Kids in Brooklyn,” and “Here Comes The…,” were all terrific, and the more I heard, the more I though that Butch might have his best album on his hands.

Apparently, though, Butch wasn’t feeling the same way. Despite the constant surge of great material that was finding its way to his Myspace page that fall, the songwriter claims he was struggling with writer’s block at the time and was having trouble finishing songs at all, let alone writing about anything meaningful. He was still touring and putting on a brave face, though, and from how great the shows were sounding, it would have been hard for anyone to notice that something was wrong. On November 23, 2007, Butch took the stage at Maxwell’s in Hoboken, New Jersey to play a slew of new songs in an intimate and acoustic setting. During the show’s standout moment, a chilling take on another recent Myspace demo called “Ships in a Bottle,” Butch bled emotion onto the stage, singing the song’s chorus like it was all he had left:

I don’t want to know if there’s another part of me, don’t want to feel if I’m alive

Don’t want to smell the bed where you used to sleep, I’m gonna miss it again

I just want to walk away from the ashes, and take the fact that I’ve been burned

And maybe let you know I’m still standing, and if you miss it again, I’m around.

It was prophetic and ironic in the cruelest sense. One night, those were just lines in another heart-wrenching break-up song. The next day, Butch’s life was ashes and he had been burned. Suddenly, everything had changed. No one was talking about a new album or a world tour. Everyone was just wondering just how much Butch had lost in that fire, both quantifiable and unquantifiable, and what our favorite songwriter was going to look like when he finished digging through the wreckage.

It would be almost an entire year before Sycamore Meadows—named after the street where Butch’s house had once stood—would finally arrive, but when it did, it was worth the wait. For me, it was also a confusing release, though. By the time Sycamore Meadows arrived, I had heard 10 of the 12 songs already, either as Myspace demos or live recordings from the only shows Butch had played that entire year (he cancelled his “one man band” tour with Jesse Malin to re-record Sycamore Meadows from scratch, but still played a pair of Atlanta dates). When you’ve been listening to raw versions of songs for months at a time, it’s hard to get on board with the more fleshed out studio versions, and that was the case for me with Sycamore Meadows, at least for the first few days. Some of the songs—“3 Kids” and “Vessels,” in particular—hadn’t changed much, and actually really benefited from a bit of extra studio work. They’re still two of my favorite Butch songs, the former because it’s arguably Butch’s best live song, the latter because it distills heartbreak so thoroughly into a single line: “we don’t get along anymore.”

Other songs got more dramatic transformations that felt more jarring. “Ships in a Bottle” was one that took me a long time to really enjoy on record, simply because I had listened to it so many times as a blisteringly emotional acoustic song that I thought hearing it covered in horns, pianos, 1970s electric guitar tones, and back-up vocals lessened the impact of the lyrics or Butch’s vocal delivery. (It didn’t.) Nowadays, I adore both versions of “Ships in a Bottle,” but I also understand that the full-band studio recording is a much better sonic match with the rest of Sycamore Meadows, which is a lively, organic, and fascinating record, as loaded with interesting musical textures as any record in the Butch catalog. Back then, though, I needed some time to adjust, and as a result, I really spent a lot of time with the songs that were actually new to me.

One of those was “The Weight of Her,” which I had technically heard prior to the album’s release, but not in a live or acoustic version (it was the first single). To this day, “The Weight of Her” remains my favorite opening track on any Butch record, thanks to a chorus that deftly balances power pop with the folk and Americana influences that were introduced on the last record. I like to think of Sycamore Meadows as Butch’s “classic singer songwriter” record. Walker makes some very obvious tributes to his major idols throughout this record, and those result in a collection of songs that feel wonderfully varied without ever sacrificing a cohesive feel. For example, one of the album’s ballads, the electric-piano-and-drum-machine slow-burn of “Passed Your Place, Saw Your Car, Thought of You” is a dead-ringer for My Aim is True-era Elvis Costello. Similarly, “The Weight of Her” is Butch’s attempt to write a feel-good rock song in the vein of Tom Petty’s 1977 classic, “American Girl.” Needless to say, it works.

The other major 1970s influence at play here appears on penultimate barnstormer, “Closer to the Truth and Further from the Sky,” which rapidly became my go-to favorite song on Sycamore Meadows. For awhile, I couldn’t put my finger on precisely why I loved the song so much, I just knew that I couldn’t stop listening to it while I drove around my hometown that year as fall turned to winter. I felt like this was a different kind of song for Butch, falling somewhere between classic heartland rock and age-old folk music traditions; I knew that couplets like “Roadside venue all papered in menus in a town that forgot its own name/We were hungry for anything that had a pulse as we freed ourselves from the rain” sounded timeless, even from the first time they drifted over my iPod headphones and stopped me in my tracks; and I knew that the song’s chorus was arguably the best, most anthemic thing that Butch had ever written.

The more time I spent with the song, the more obvious the inspiration behind it became: we’d had a Petty song and a Costello song, and now here was Butch attempting at a Bruce Springsteen, Born to Run or Darkness on the Edge of Town-style anthem. On record, Butch removed the drums, leaving it more stripped down than we expect an epic, tear-down-the-walls hymn to sound. It doesn’t matter: “Closer to the Truth” remains a pulse-pounding and life-affirming song that stands as a “Badlands” or a “Born to Run” for a modern age. When I first heard it, I wasn’t the Bruce fan I am now, but “Closer to the Truth” made me look closer. A month later, I was diving headfirst into Springsteen’s back catalog and the rest is history. For those that know me around these parts, that says a lot about how big a role this song played in my life, and it remains my favorite part of this album.

Listening back as I write these words, with iTunes play counts of “100” or more staring at me from every song on this record, I can’t believe I ever had reservations about Butch’s production and instrumentation choices. Sure, “ATL” gets a heavier layer of reverb than the demo had, but the resulting product is only more haunting and ghostly as a result. And yeah, “Here Comes The…” didn’t need a Pink guest feature, but who can fault that decision when it earned Butch some well-deserved mainstream attention? (Pink also deserves to be on this record, if only because she met Butch at the ruins of his old house with a gorgeous Gibson Les Paul.) Elsewhere, older songs were either built up (“Summer Scarves,” a wistful and melancholic tune which evolved from an early electric guitar solo song into a full-band number with an unorthodox oboe intro) or left sparse (“Song for the Metalheads,” an acoustic guitar/harmonica ditty where Walker memorably croons, “the record business is fucked, and it’s kind of funny”), while another brand-new song (“Ponce De Leon Ave.”) added some percussive, Prince-flavored funk-pop into the middle of the album to mix things.

But even despite all of its wonderful new directions and beautifully refined twists on the older ones, Sycamore Meadows always comes back around to one song and that’s “Going Back/Going Home.” The first thing that Butch wrote after the fire, the song that broke the ice of his alleged writer’s block and convinced him that he had something to say again, something to prove, “Going Back/Going Home” is, I think, the song from this record that remains nearest and dearest to Butch’s heart. To this day, he plays it at every live show, always making jokes about fucking up the “rap” section—halfway through the song, he does an entire, spoken-word recap of his life and his trials and tribulations in the music industry, all in less than a minute and a half—and always inspiring massive cheers when he sings the final couple of lines: “Every time I come back in this town I know/That I finally know the difference between going back and going home.”

“Going Back/Going Home” is a bittersweet song, not just because of the personal meaning it has to Butch, but also just because the lyrics paint portraits of people leaving behind something broken to start anew (“She tells her song she did the best she could as she buries dad/Maybe he’ll grow up to be a man, unlike his father did,” Butch sings in one of the verses). Regardless though, the ultimate impact of “Going Back/Going Home” is a hopeful and resilient one. The triumphant guitar riff, punctuated here by sparkling bells and a simple acoustic chord progression, feels like a rise from the ashes, and that’s really what this album is all about. Upon release, many—myself included—were ready to call Sycamore Meadows a sequel of sorts to Letters, but I no longer think that’s the case. This record is its own beast: a similar blend of loud and soft, sarcastic and serious, introspective and forward-thinking, to be sure, but with an entirely different musical palette and a mood that—despite the broken resignation of “ATL” and “Voice and Piano,” the album’s dream sequence of a hidden track—feels far more interested in leaving the past behind than languishing in it. Letters will always be my favorite Butch Walker album, largely because of when it first came into my life, but Sycamore Meadows is a damn-near perfect record on its own, and, because of what it meant to Butch, arguably the most “important” work of his career. It’s got “classic” written all over it.

Closer to the Truth and Further from the Sky

Closer to the Truth and Further from the Sky