What’s the first song you ever loved? If we’re being really honest, the answer for most of us is probably something like “Happy Birthday,” or “Jingle Bells,” or a lullaby our parents sang us when we were young. Maybe it’s something we heard in our favorite childhood TV show or Disney movie, or a nursery rhyme song, or some silly novelty ditty we learned from the other kids at daycare. Me, though? I can’t really remember ever caring about music in any fashion until I heard “Mr. Jones.”

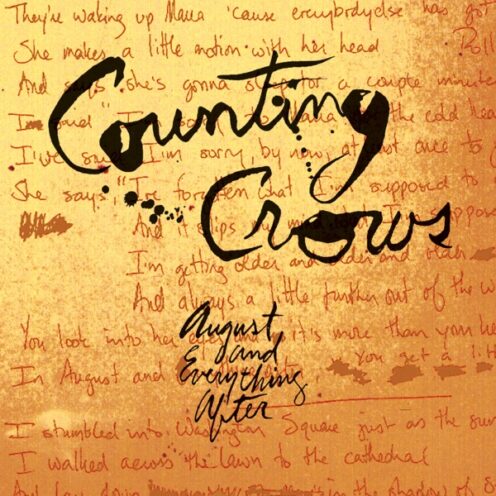

Counting Crows are the closest I can come to saying I’ve loved a band for my entire life. Their debut album, 1993’s August & Everything After, came out 30 years ago today, a few months before my third birthday. At some point, a copy of it came into my family’s possession – and more importantly, into our Ford Expedition. In the backseat, headed home from some family day trip, I watched as my brother slid the album into the CD player and skipped to track 3.

In retrospect, “Mr. Jones” doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that would appeal to a young child’s brain. It’s verbose and meandering and takes forever to get to the chorus. Adam Duritz sings a lot of words that didn’t register any meaning to me at the time: things like “New Amsterdam” and “flamenco dancer” and “Bob Dylan.” And boy, I remember being baffled – truly baffled – by this man’s claim that grey was his favorite color. Surely, he was a liar, or maybe even crazy.

But for as bewildering and strange as I found “Mr. Jones” to be, when the song finally wound around to the hook, it enraptured me. “Mr. Jones and me/Tell each other fairytales/And we stare at the beautiful women/She’s looking at you/Oh, no no, she’s looking at me.” The melody was warm and golden and welcoming, and I fell in love with it right away. Soon, every time I was in that car, I wanted nothing more than to get the CD with the yellow cover out of the center console, skip to track 3, and take that ride again.

I loved “Mr. Jones” the way a child typically loves music – quickly and without reservation, but also without much curiosity. I knew I liked that song, but it never occurred to me that I might like other songs on the same album. Whenever August & Everything After went into the CD player, it was always straight to track 3. I presume I heard the rest of the album play through in the car on multiple occasions, but it never registered. As far as I was concerned, Counting Crows were just the band that sang “Mr. Jones.”

It would be a solid decade before I truly sought out August & Everything After to give it an engaged listen. Counting Crows flitted in and out of my life in the interim: I loved “A Long December” and remember my brother playing Recovering the Satellites on a road trip the family took to Canada one summer. Fast-forward to the early 2000s and “Big Yellow Taxi” was a source of joy for me any time in came up on the radio. Around the same time, “Round Here” was part of the small mp3 collection on the family computer, and thus came up on Winamp whenever I was listening to music. But it wasn’t until early 2004 that I really forged a true bond with the band that would change my entire life.

My gateway into Counting Crows – not as a singles band, but for real – was the 2003 greatest hits collection Films About Ghosts. I bought it on a whim when I was 13 years old, trading the Kmart cashier $20 of that year’s Christmas money for the CD with a vibrant red and orange tree on the cover. I did it, mostly, because Films About Ghosts had a brand-new Counting Crows hit on it called “She Don’t Want Nobody Near” that I loved so much I knew any price would be worth getting to hear it every single day – usually more than once. But I also did it because I was becoming curious about music. In this case, that curiosity was simple: I liked every Counting Crows song I knew, so I wondered what other treasures might be hiding in the tracklist of their supposed best of.

Films About Ghosts unlocked Counting Crows for me in a way no band had ever, up to that point in my life, been unlocked. I was surprised to find that, for how much I loved the radio songs, my favorite tracks on this compilation were the more under-the-radar cuts I’d never registered before. I loved the adrenaline rush of “Angels of the Silences” and the crescendo of “Anna Begins.” I was bowled over by the poetry of “Mrs. Potter’s Lullaby,” by the nameless yearning of “Recovering the Satellites,” by the resigned, quirky sadness of “Holiday in Spain.” I felt cultured hearing and enjoying the Grateful Dead cover, and like I was in on some secret when I listened to the long-lost “only the real heads know” b-side “Einstein on the Beach.”

Falling in love with those 16 songs had the effect of supercharging my curiosity around this band and everything they were. I read and re-read the essay about them included in the Films About Ghosts liner notes and memorized the names and roles of every band member, past and present. I noted little tidbits of trivia – like the fact that Counting Crows drummer Jim Bogios had previously worked with Sheryl Crow and Ben Folds. I joined the countingcrows.com fan community and started reading Adam’s blogs and posting on the message board. I found a site called anna-begins.com that had download links to a whole slew of b-sides and demos. I eventually started collecting Counting Crows live bootlegs.

Most importantly, I went back to the albums. At that point in time, there were four Counting Crows full-lengths on the market, plus the Across a Wire double live album. I snagged my parents’ copy of August & Everything After from the CD shelf in the living room and ventured into the basement to dig up my brother’s dusty Recovering the Satellites CD. I scooped a second-hand copy of This Desert Life off Amazon.com and bought a shiny, brand-new copy of Hard Candy from the nearest Borders Books & Music. I scored the Across a Wire set from the FYE at the local mall. I brought them all back to my childhood bedroom and proceeded to listen to them over and over and over again, learning every nook and cranny of every single song.

I didn’t realize at the time, but I was learning the language of being a music fan – a language I’d repeat again and again over the course of the ensuing two decades. At school, I was learning the usual subjects that a seventh grader learns. But when I came home, I was schooling myself – and finding out about something that would be far more important in shaping me. I learned so much, in particular, from Adam Duritz, who taught me that it was okay to be vulnerable and earnest, and that being in touch with your emotions didn’t make you any less of a man. He taught me about poetry and language, and about how beautiful they could be even without the music around them. He taught me that singing like your life depended on it could be the most cathartic thing in the world. And he taught me that music could be more than just background noise, but a vitally important companion for all of my days. He was my first rock ‘n’ roll hero.

Back then, I never could decide which of those first four Crows albums was my favorite. August was the hit machine, and Hard Candy had this summertime magic to it that pulled out all the things I loved about the season and deepened them. But This Desert Life boasted all these weird little jagged edges that my teenage brain sent me back to again and again as I tried to figure them out, and Recovering the Satellites just straight up rocked. For 10 months of 2004 – right up until a little album called Futures came along – I listened to little else but Counting Crows.

Nowadays, I’m still not sure I have a favorite Counting Crows album, but August & Everything After feels like the one worthy of making it onto a “best albums of all time” list. While “Mr. Jones” was the first song to catch my ear, and while “Round Here” was my favorite song from the album for a long time, I now view the big singles from August & Everything After as being almost secondary to what makes the album so special. This record may have sold 8 million copies and become a shared reference point for countless members of the Gen-X and millennial generations, but when you actually listen to it, it doesn’t sound like the kind of music that is meant to be shared as some sort of grand communal experience. Rather, August is a deeply moving album about overpowering loneliness.

“I wanted so badly, somebody other than me/Staring back at me/But you were gone, gone, gone.” Duritz sings those lines at the start of “Time and Time Again,” a song so deeply lonely that the narrator starts wishing he could rewind to the moment where his partner walked out the door and replay it until the sensation of being left behind fades to indifference. On “Raining in Baltimore,” he’s howling about being three-thousand-five-hundred miles away from home and wishing he could shrink the world to be closer to the people he loves. Or maybe he’s just wishing for a phone call – to hear their voices through the static. Actually, there are a lot of wishes in that song: for big towns and plane rides, or for a raincoat just to keep him dry. Every wish sounds lonely, at least the way Adam sings them.

Most of the albums I love bring me joy and pain in equal measure. There’s something about the music you invest in heavily that just tends to do that – to collect all the memories that ring with happiness and all the memories that ache with sadness and smash them together into this weird cocktail of emotions that hits you a little differently every time you listen. Perhaps no album I know does that more for me than August & Everything After. Hearing Duritz sing these songs hurts, even if 30 years have gone by and the young dreadlocked man who wrote them has aged into a guy pushing 60. But I guess that says something about the timelessness of the record, too – about how, no matter how many years pass, there will always be a universal language to the way Adam sings about falling in love with a close friend and having it all go bad (“Anna Begins”), or about the melancholy clarity you find when you’re driving alone late, late at night (“Sullivan Street”), or about stepping out the front door like a ghost into the fog where no one notices the contrast of white on white.

I’ve heard August & Everything After so many times over the past 30 years that I could probably sing every instrumental line back to you from memory – let alone every word to every song. Sometimes, you hear pieces of music so many times that you almost don’t need to listen to them to experience them, because they’re already locked in your brain. This album is like that for me, but that doesn’t mean I’ve gotten tired of hearing it. To this day, when it’s raining, or when it’s the first day of chilly fall weather, or when I’m up way too late, I still reach for August & Everything After, and it still makes me feel all those things it did when I was a 13-year-old kid just trying to understand the technicolor emotions of a grown man’s world.

I know now that there’s no way to understand that world, or the way it will hurt you and humble you, confuse and confound you, enrage you and drain you, and maybe, occasionally, make you whole. But the magical thing about August & Everything After is that, for as good as it is when you’re young and trying to comprehend the world of adults, it’s even better when you grow up and start to realize that the more you live, the less you know. It’s an album that resists the usual dichotomies: happy and sad, right and wrong, black and white. Maybe that’s why Adam’s favorite color is grey, because he loves dwelling in those messy in-betweens that tend to reveal themselves as you make your way deeper into adulthood. It’s why the album’s most triumphant-sounding song has a chorus that proclaims something as sad as“All your life/Is such a shame, shame, shame,” and it’s why “Round Here” sounds so desperate even though a lot of it is about the freedoms that kids view so idyllically when they dream about getting older: the freedom to do what you want, go where you will, stay up very, very late.

”You’re told as a kid that if you do these things, it will add up to something,” Duritz once said about “Round Here.” “You’ll have a job, good life. And for me, and for the character in the song, they don’t add up to anything, it’s all a bunch of crap. Your life comes to you or doesn’t come to you, but those things didn’t really mean anything. By the end of the song, he’s so dismayed that he’s screaming out that he gets to stay up as late as he wants and nobody makes him wait; the things that are important to a kid –you don’t have to go to bed, you don’t have to do anything. But they’re the sort of things that don’t make any difference at all when you’re an adult. They’re nothing.”

Starting an album on that note of emotional atrophy is a fascinating decision, and I think it led me to misinterpret “Round Here” for a long time. When I was young, I heard the song as defiant, which makes sense: I was a kid wondering what it would be like to have the freedoms that Adam was shouting out in the song, so I heard resilience there. But that’s the hope of youth, right? That life will be an easy straight line: Your idealized vision of the future will come true, and all the things you looked forward to will be as great as you envisioned them, and no one you love will ever let you down. But hearing the album at 32 is different than it was hearing it at as a child in the back of his parents’ car, or as a teenager up in his adolescent bedroom. Now, I hear all the uncertainty, all the hard-earned lessons, all the bruises and battle scars. And hearing those shades in these songs as someone who’s had his heart broken, and who’s seen his childhood dreams die, and who’s had people he loved deeply let him down and drift out of his life, it’s only made me love this album more.

On “A Murder of One,” Duritz intones, “We were perfect when we started/I’ve been wondering where we’ve gone.” These days, I like to think that he was singing about the innocence and wonder of youth there, and how you lose it as you grow up. You can try to cling to the simplistic beauty of that time of your life. But as the divination phrase that inspired this band’s name states, “If you hang on to the flimsiness of anything, you may as well be standing there counting crows.”

August & Everything After is an album about growing up, about losing the wonder of youth, about wondering where it’s gone, and about trying to figure out how to carry on without it – no matter the heartbreak and rainstorms that brings. 30 years ago, the album was a pop sensation, but it was never built to be one. It was never built to do that thing that pop songs do, where they burn brightly for a moment in time and then burn out. Instead, this album is built to age with you – to tell you new things about your life as you go through the process of living it. And for that reason, I’m so grateful it’s the album I’ve loved longest. More than any other piece of art, it’s a reflection of where I’ve been and what I’ve learned along the way. I can’t wait to hear how it sounds at 40, and what it might teach me on the journey to getting there.

A Murder of One

A Murder of One