Over the course of the past 10 years, few albums from the 2000s have stuck with me quite like The ’59 Sound. One of the undeniable truths of being a consummate life soundtracker is that most of your favorite albums end up being inextricably linked to certain periods of time. You play those records so much when they’re new to you that they become a collage of moments and memories from your life. It’s a beautiful thing when that happens, but it also tends to mean your favorite LPs eventually fall out of regular rotation, as you reach for new music to play that role for new moments and memories. Most of my favorite albums fit into this category. My other 2008 classics—records like Butch Walker’s Sycamore Meadows and Jack’s Mannequin’s The Glass Passenger—are albums I revisit only every month or two, not because I don’t love them, but because they hold so many pieces of my past self within their songs. Those albums could never be life soundtracks to me today, because they already played that role at such vivid and crucial junctures of my life.

The ’59 Sound is different. It’s the rare “favorite record” in my life that isn’t tied to any one specific moment or season or year. It’s a record that has grown with me over time, one that has meant a dozen different things to me from one year to the next. Where other records I loved back then have drifted more into the background, The ’59 Sound is a record I’ve played regularly—probably once every couple weeks, at least—for the better part of the past decade. A part of the reason is probably my initial indifference to the album. The ’59 Sound got a lot of hype in 2008, but my first listens told me it was something dated and backwards-looking: songs stuck in the past that didn’t have relevance to my present. (Note: this opinion is my worst first impression of all time.) Because I was never infatuated with this album like I was with many of the LPs that came out around the same time, I never “wore it out” in the same way.

A bigger part, though, is the album’s thematic structure. In the early years, even after I started to fall in love with this album, I heard Fallon’s evocations of rock ‘n’ roll greats—coupled with imagery of summer nights and Ferris wheels—and mistook them for pure romanticism. To my ears, The ’59 Sound was a modern take on Bruce Springsteen’s The Wild, The Innocent, and The E Street Shuffle: a record about bumming around on the beachside streets of Jersey, and about a time in life when responsibility was still far afield. Or maybe that’s just what I wanted to hear.

The great thing about Fallon’s writing on this record is that there is so much more than what you see or hear on the surface the first time you listen. The references, it turned out, weren’t just allusions and evocations to rock ‘n’ roll greats: they were thematic devices, meant to add color, texture, and feeling to the narratives. As for the stories, Fallon’s aren’t always easy to follow—at least not at first. On this record especially, Brian Fallon didn’t write in a linear fashion. Songs like “Old White Lincoln” split their narratives into flickers of memory and sound and song, because that’s often how we remember things: lighting cigarettes on parking meters; racing fast cars; hearing something friendly and familiar crackle through the radio; feeling the nights getting warm; seeing a sundress hanging on a clothesline in a girl’s backyard; high top sneakers; sailor tattoos; classic cars; movie screens; the top rolled down on a Saturday night. Memories don’t always follow a logical through line. They play less as movies in our minds and more as stream-of-consciousness montages. The songs on The ’59 Sound capture that feeling of nostalgic reverie more accurately than anything else I’ve ever heard, but they can also make the record inscrutable on early listens. As someone raised on narratives in songs, I was expecting Fallon to be a Spielberg when he was really a Tarantino.

In an oral history of The ’59 Sound published in June by The Ringer, Fallon reveals that much of the album was written in a mad dash after the band arrived in California to start recording. Fallon says he wrote four songs—“Meet Me By the River’s Edge,” “Here’s Looking at You, Kid,” “The Backseat,” and “Old White Lincoln”—in the space of a week, all at the kitchen table of the band’s minuscule rental apartment. That “crunch time” element probably adds to the feverish intensity of the songwriting, but it also meant that Fallon didn’t have much time to second guess himself or iron out the finer details of his work. As a result, he gave us a all a maze of his memories to wander through—one which, in turn, probably morphed into a maze of our own memories. That was always my favorite thing about The ’59 Sound: you could hear that reference to “humming a song about 1962” in “Great Expectations” and remember good times spent singing along with “Night Moves” on the radio in your best friend’s car. Fallon’s songs were vivid enough to be authentic, but their non-linear structure left plenty of space for them to become Rorschach tests for every individual listener.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gained a better understanding of what The ’59 Sound means. To a certain extent, Fallon was a guy stuck in the past on this record. Few albums wear their nostalgia so proudly. But he’s not stuck in the past because he’s romanticizing it, or because he’s mourning the loss of rock ‘n’ roll as a dominant cultural force. Instead, he’s living in the past because he’s a little bit scared of what the future might hold. Beneath all the references and vinyl pops and tributes to bygone days is a vulnerable record about the journey from youth to adulthood and about how scary and painful it can be. Who wouldn’t want to look back when growing up means hearing that your friends died in a car wreck on a Saturday night, or sitting in a diner getting consolation sighs from the waitress because she knows you’re nursing one hell of a broken heart? Except now the Tom Petty and Counting Crows songs don’t offer the same refuge as they used to, because instead of getting lost in them, you’re wondering what it would be like to hear them coming over the radio during a car crash, right before you stopped breathing.

Listening 10 years later, The ’59 Sound carries the bittersweet sting of that moment in life when you finally realize you’re not a kid anymore. That ending comes in many different forms for different people. It might happen because you get your heart broken and everything that once seemed black and white explodes into a kaleidoscope of color and pain. It might happen when you leave home for the first time and become unmoored from everything that has stabilized your life up to that point. It might happen because you realize that youth can’t protect you from mortality. “But I used to wait in a diner a million nights without her/Praying she won’t cancel again tonight.” “Don’t wait too long to come home/My how the years and our youth pass on.” “Young boys, young girls/Ain’t supposed to die on a Saturday night.” So many of Brian’s lyrics are painful tributes to things that are gone and aren’t coming back. Nights out in the Jersey rain, just waiting for something to happen; girls in red dresses sneaking out of their windows to come out with you; parties that rage until the good feeling dies. If youth is wasted on the young, it’s because you don’t cherish the magic of moments like these until you can’t have more moments like them. Sometimes, on The ’59 Sound, it feels like Brian is trying to capture as many of those small moments as possible, because if they’re in the songs, then maybe they aren’t really gone.

For all its nostalgia, though, The ’59 Sound is not a record about holding onto youth. Actually, it’s the opposite. Instead of holding on, it’s a record about letting go. By the time the album spins around to “The Backseat,” youth has morphed from a collage of great expectations and Ferris wheel nights into something claustrophobic and cramped. “You know the summer always brought in/That wild and reckless breeze,” Brian sings in the chorus, sending up the wildness of being young one last time. But then he adds the qualifier: “And in the backseat, we just tried to find some room for our knees/And in the backseats we just tried to find some room to breathe.” Youth means sitting in the backseat of your own life, while someone else drives you. It’s effortless and carefree and it shields you from the dangers and pains of the world. But eventually you outgrow it. Your knees start pushing against the leather of the seat in front of you. You yearn to climb into the driver’s seat to take control—or at very least, the passenger seat, to be someone’s co-pilot. Taking that leap is a risk, because it means shouldering the responsibility for everything that happens out on that great big highway of life. It means dealing with the breakdowns and car wrecks and detours and bumps. But it also means freedom: the ability to take whichever exit you want, to drive as fast as you need, to go where you will. “The Backseat” captures all this pain and possibility so perfectly that, every time I listen, I swear it hurts a little more, while also making me smile a little wider.

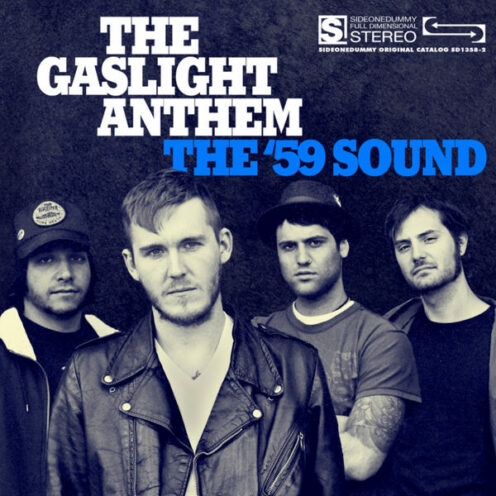

The ’59 Sound was a big moment in rock ‘n’ roll even back in 2008. Listeners loved it; Bruce Springsteen endorsed it; Pitchfork gave it an extremely favorable review. But when it came time for publications to list their favorite albums at the end of the year, it was nowhere to be found. Albums from bands like Fleet Foxes, Portishead, Deerhunter, and TV on the Radio stole the lion’s share of the honors. 10 years later, The ’59 Sound feels more important than all those records. It’s gotten more anniversary buzz, a sold out reunion tour with insanely passionate audiences, a note-perfect oral history, and countless tributes from fans. In retrospect, it feels like the 2008 classic. There were more acclaimed records and there were bigger sellers, but The ’59 Sound is a textbook “that album changed my life” kind of record. Maybe that’s just because the themes are so relatable, so universal, so timeless. Maybe it’s because the people to whom this record means the most were like me, finally climbing from the backseat to the front seat right around the time this album released. Whatever the reason, The ’59 Sound became an undisputed classic. For a lot of kids, it turned The Gaslight Anthem into the kind of rock ‘n’ roll heroes that Fallon was quoting in the songs.