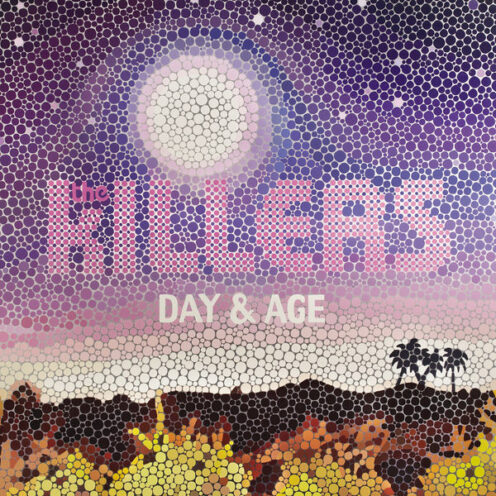

I believe “What the hell happened?” was my first reaction upon hearing Day & Age, the third album from The Killers, for the first time. This record didn’t compute for me. It was bizarre and misshapen, a mess of ideas that never coalesced into anything that made sense as a unified work of art. It sounded to me, on first listen, like a B-sides record. If The Killers hadn’t released an actual B-sides collection just a year before, I might have wondered if the band just gotten lazy and pulled out some ideas they’d shelved for earlier records. But apparently Day & Age was the statement the band really wanted to make at that time, and what an odd statement it was.

10 years on, Day & Age continues to baffle me—though I’ve since come to appreciate it for its playful, genre-hopping excursions. It’s an album where the band sounds like they have no legitimate idea what they are trying to accomplish. Brandon Flowers said Day & Age was “like looking at Sam’s Town from Mars,” the kind of meaningless statement that interviewers love to print but that doesn’t really shed any light on the creative process. Some fans claimed that Day & Age sounded like a mix of the first two Killers records—between the synth-driven 80s throwbacks of Hot Fuss and the Springsteenian heartland rock of Sam’s Town. But Day & Age sheds much of the dingy darkness and desperation that made those records so unique. It is a bright, technicolor-hued arena rock extravaganza, bearing only occasional resemblances to what The Killers were before. It would be considerably more accurate to say that Day & Age sounds like a mix between U2, Elton John, and The Lion King.

Undoubtedly, Day & Age leans toward pop where the previous two records leaned toward rock. You can thank or blame producer Stuart Price for the change. Price, best known for producing Madonna’s 2005 LP, Confessions on a Dance Floor, certainly made The Killers sound a little like Madonna here. The closest Day & Age comes to a house style is “80s dance club”—a style that sometimes suits the band (the interstellar new wave of “Spaceman”) and sometimes doesn’t (first single “Human,” which sounds like Sam’s Town’s “Read My Mind” remixed as a less interesting pop song). But the oddest thing about Day & Age is how frequently it shirks that style for seemingly random tangents. Opener “Losing Touch” plays like a piece of a different Killers record, blasting out of the gate with Dave Keuning’s signature guitar roar and building to something that feels like rock ‘n’ roll gospel. “I Can’t Stay” is a sunny, Caribbean-flavored island pop jam—complete with steel drums. And closer “Goodnight, Travel Well” is a creeping, dark-as-night slowburn that sounds downright jarring at the end of such a bright, colorful record.

There are ideas on this record that shouldn’t work, but do. The clearest example is “This Is Your Life,” which combines African-style chanting, harpsichord, and keys for one of The Killers’ most rousing stadium anthems. It forms the core of the record, along with “A Dustland Fairytale,” one of the Killers’ very best songs. “Fairytale” combines the widescreen heartland rock fantasies of Sam’s Town with Price’s larger than life production, and the result is a genuine epic. It’s the song that paved the way to Battle Born, a record I still consider to be The Killers’ best. These songs are big, and they are meant to be taken seriously. “This Is Your Life” aims for stadium-sized uplift, while “A Dustland Fairytale” is as personal as Flowers ever got in his writing (at least until last year’s Wonderful Wonderful). Written about Flowers’ parents, the song tackles decades of history: the moment the two fell in love, his father’s decision to quit drinking, and his mother’s battle with brain cancer, which she would lose a little more than a year after this song arrived. It’s a heavy, poignant centerpiece to the album, and it feels almost blasphemous to stack it alongside lightweight pop confections like “I Can’t Stay” and “Neon Tiger.”

On first listens, the scattershot randomness of the Day & Age track listing was what I struggled with the most. There were wonderful songs here, but they were often placed alongside tracks that, to my ears, sounded like glorified outtakes. Flowers may love “Joyride,” to the point where he thought it would be the album’s big hit. But the song’s playful, sax-driven jungle vibe just doesn’t work alongside the more rousing one-two punch of “This Is Your Life” and “A Dustland Fairytale.” Similarly, “I Can’t Stay” is a pleasant enough diversion, but its extremely low-stakes vibe kills the do-or-die momentum established by the two preceding songs. By the time the album reaches “Goodnight, Travel Well,” it feels like it’s reaching for some sort of epic catharsis that it hasn’t entirely earned. Early on, I found the song borderline unlistenable, and would always turn the album off after “The World That We Live In.”

I changed my mind on “Goodnight, Travel Well”—and on the album as a whole—after reading a review that compared Day & Age to Achtung Baby. Just like U2’s big 1991 left turn, Day & Age was caught between the brightness of dance-pop and its’ creators yearning for darker textures. And just as Achtung Baby had ended by crashing its discotheque party into the gloom of “Acrobat” and “Love Is Blindness,” Day & Age ends with its own unflinching descent into darkness. (Coincidentally, Achtung Baby and Day & Age both came out on the same day, exactly 17 years apart.)

The U2 comparison made sense to me, and it made me see Day & Age for what it was: a bold experimental gesture from a band that, clearly, was never going to sit still. I had visions, at the time, of The Killers becoming the kind of rock band that would follow its muse regardless of whether doing so was popular with critics or mainstream listeners. Here was a band that would be brave enough to have a decade like U2 did in the 90s, with albums like Zooropa and Pop. Here was a band that, like R.E.M., might be able to string together a series of albums as different and uniquely rewarding as Automatic for the People, Monster, New Adventures in Hi-Fi, and Up.

That vision has faded in the years since, for a few reasons. First, Brandon Flowers has proven that he is too bothered by what critics and listeners think. It’s fair to argue that the pop-heavy sound of Day & Age is partially a reaction to the critical thrashing that Sam’s Town received when it was released. After Battle Born was written off by critics, Flowers turned his back on that album, too. He’s not fearless enough to build The Killers into the kind of dynamic, unpredictable career band that I thought they could be after settling into this album.

Second, it’s entirely possible that bands of that wandering ilk just can’t exist anymore. Social media and streaming have changed the way we consume and react to music, in a way that would have killed oddities like Zooropa or Up on arrival if they came out today. Listeners jump to judgments too quickly. The die is cast on the narrative of a new album at such a rapid speed that more informed, nuanced, and time-considered takes usually don’t get the opportunity to marinate. Just look at what’s happened with the last two albums from Arcade Fire, a band that has made an active play to transition into its “weird” era. Once the buzziest indie rock band on the planet—and a Grammy Album of the Year winner, to boot—Arcade Fire now have trouble selling out their tour dates. Rock bands, simply put, are not granted the artistic leeway they once had.

Third, and perhaps most unavoidably, The Killers no longer seem poised to be the long-term career band I would have bet on them being 10 years ago. The band slowed down after this album, waiting four years to deliver 2012’s Battle Born, and then taking an additional five to finish 2017’s Wonderful Wonderful. Dave Keuning was barely involved with the latter, and no longer tours with the band. Bassist Mark Stoermer has also retired from touring. Flowers promises that another Killers album is coming—and sooner than we might think. But it’s impossible to picture this band as the next U2 anymore, given the fact that U2 have only survived as long as they have by keeping the same four-man lineup and making decisions as a unit.

The result is that, 10 years later, what once looked like the promise of an unpredictable musical future now looks like a career anomaly. Day & Age is the only album in the Killers catalog without a clear identity. Hot Fuss was the scrappy, 80s-influenced debut. Sam’s Town was the “serious” follow-up, a conscious attempt to make a masterpiece. Battle Born was the classic rock LP, drawing influence from artists as varied as Queen, The Velvet Underground, and Journey. And Wonderful Wonderful was the family album, the sound of Flowers taking stock of marriage, fatherhood, and middle age. Day & Age is not constrained by the boundaries of things as silly as “theme” or “influence.” It is proudly disconnected, lacking cohesion in such a blatant fashion that it’s hard to imagine the result was not intentional. It’s still weird, still jarring, still frustrating to listen to. The difference between now and the first time I heard it is a matter of perspective. Back then, Day & Age sounded like one of my favorite bands losing the plot. Today, with the future of The Killers in doubt and with the term “mainstream rock” existing only as an oxymoron, the album sounds creative and restless and confident and loose. It’s a glimpse into a future that never happened, and I still hope that, someday, we’ll get the next chapter.