“I never really gave up on breaking out of this two-star town.”

When Brandon Flowers sang those words back in 2006, he completed a rock ‘n’ roll rite of passage: that of penning a great escapist anthem. The album he was working on at the time, the sophomore Killers LP Sam’s Town, was in part an homage to Bruce Springsteen, so it made sense for there to be a song like “Read My Mind” that channeled some of the pulling-out-of-here-to-win energy of Born to Run. When Flowers sang that song, you could hear in his voice the yearning to get out and find something better. You didn’t know where he was going, but you felt like he was probably never coming back.

That’s the thing about escapist rock ‘n’ roll anthems, though: they only tell one part of the story. For Flowers, Sam’s Town ultimately functioned as a show of rock star mythmaking. Here was this charismatic frontman, someone who’d arrived on the scene with all the pomp and showmanship you’d expect from a guy raised on British rock and tested on the proving grounds of the Las Vegas scene. Sam’s Town was his origin story, the moment where he flashed back in time to who he used to be, and to where he used to be. But who you used to be lives in your bones, and so does the place you’re from. And so, while rock music tends to tell the exodus tales and the origin stories, perhaps it was inevitable that, one day, Flowers would wander back to that two-star town and see it differently.

“Inevitable” is probably the wrong word. Flowers has gone on record saying that Pressure Machine, the seventh full-length album from The Killers, would never have come to be had it not been for the pandemic. Still, listening to these songs, there’s something about them that makes you feel like they were always going to find their way out eventually. There’s too much history, too much memory, too much pride, too much pain in these songs. I somehow doubt that the emotions and ideas behind them could have stayed locked in Brandon Flowers’ head forever.

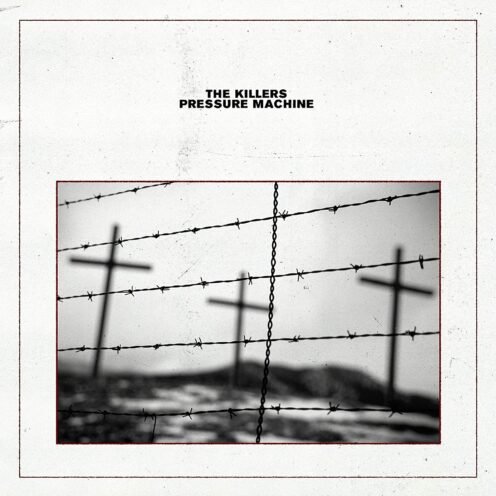

Pressure Machine, like Sam’s Town, is about the place where Flowers grew up: the small town of Nephi, Utah, population 6,400. Neither album makes it seem like a particularly glamorous place. But where Sam’s Town painted Nephi as a trap to be escaped, Pressure Machine sketches it in more empathetic light. For some people, these types of small towns are all they will ever know. Every town of this ilk has “born here, live here, die here” types, people whose every joy and every tragedy will be set against the backdrop of this one dot on the map.

It’s easy to be judgmental about people who hail from rural small towns—especially in the wake of Trump, who made those people a huge base of his electorate, and especially in the midst of a new COVID-19 surge driven in part by low vaccination rates in precisely these segments of the country. One of the things that makes Pressure Machine a truly special album, though, is that The Killers don’t judge these people at all. Nephi may have been a place that Flowers wanted to get away from, but it’s also burned forever in his soul as his hometown. So when he writes these songs and uses Nephi as the stage for an intersecting batch of stories and characters, he does so with an ability to see both the beauty and the tragedy of small rural towns.

I didn’t grow up in a place like Nephi, but I grew up within driving distance of a lot of them. When I was young, I thought the place I lived was pretty close to idyllic. Over time, I started to realize that you didn’t have to go far to find people who were experiencing pretty extreme poverty. You didn’t have to go far to trace the devastation wreaked on families and communities by addiction and the opioid crisis. You didn’t have to go far to find the ugliness of homophobia or other deep-seated ignorance. Even this year, my hometown has landed in national headlines for grotesque examples of racism and the people who cling to it as their status quo. It is far from a perfect place.

Pressure Machine is an album about this type of hometown, but it’s also more than that. It’s about loving the place you come from for how it shaped you, but also recognizing that it might be broken in a lot of ways. And it’s an album about recognizing that, even if you’ve had these epiphanies about all the busted parts hiding underneath the hood of your community, that doesn’t mean all the people who live there have had those same realizations—or ever will.

There’s privilege to the idea of escape: to knowing enough to see that the grass might be greener somewhere else, or to having the means to chase those possibilities down the highway. The characters in these songs, largely, don’t have that privilege. In “Terrible Thing,” a gay teenager mulls over suicide, lamenting how “the cards that I was dealt will get you thrown out of the game.” The narrator delivers the song from their bedroom, but they may as well be in a prison cell for how little ability they feel to change their circumstances for the better. In “Quiet Town,” local residents reckon with the tragic events that keep colliding with their community like stray meteors—from kids getting hit by trains to drug overdoses. “Things like that ain’t supposed to happen/In this quiet town,” Flowers sings. The questions float through the song like accusations: How could such fierce tragedy strike a place like this, a place that was supposed to be safe? Why didn’t Jesus and our faith protect us? Why do bad things happen to good people? Because how else do you make sense of pain on this level? “Parents wept through daddy’s girl eulogies and merit badge milestones/With their daughters and sons laying there lifeless in their suits and gowns,” the song observes, before arriving at the knife-twist: “Somebody’s been keeping secrets/In this quiet town.” In other words, maybe we didn’t know everything after all. Maybe we overlooked something we should have seen.

When a character on Pressure Machine does find a way to change their circumstances, it’s often through sheer force of desperation. In “West Hills,” after being caught “for possession of enough to kill the horses that run free in the west hills,” the narrator hits upon a foreboding promise: “If this life was meant for proving, I could use more years to live/But 15 in a guardhouse is more than I’m willing to give.” It’s an “Atlantic City” type way to end a song, with some ambiguity about the character’s intentions, but also with certainty that those intentions are going to lead to violence and calamity. And speaking of Springsteen and Nebraska, see “Desperate Things,” a song told from the perspective of a married police officer who falls in love with a woman caught in an abusive marriage—and takes matters into his own hands. Again, the conclusion of the story is left open-ended, but the words in the third verse (“I’ve got him cuffed and sweating cold/In the back of my patrol car/You forget how dark the canyon gets/It’s a real uneasy feeling”) and the music that accompanies them (an unsettling cacophony of sound that feels suspiciously like gunfire) do enough to tell you that the abusive husband ain’t getting out of that canyon alive.

Pressure Machine is as dark an album as The Killers have ever made. Many of the songs doom their characters to fates black as midnight. And yet, despite all the storm clouds that float over this album and the town it chronicles, there are still flickers of beauty there, too. The wildflowers painting the western hills as “sweeter skies and longer days of sun” herald the changing of the seasons in “Sleepwalker.” The little details of mundane domestic happiness—kids and Happy Meals and eggs cooked in bacon grease—that fill the title track. And the resilience of “The Getting By,” which closes the album on a hopeful note. “Maybe it’s the stuff it takes to get up in the morning and put another day in, son/The holds you ‘til the getting’s good.” It’s that mix of darkness and light, bad with the good, hopelessness and hope, that makes Pressure Machine the most complete and fully realized album in The Killers discography. And improbably, 17 years after Hot Fuss and two decades after they formed, it might even be their best.

In The Car Outside

In The Car Outside