I don’t know what draft I’m on of this review. I think probably my sixth. I really can’t remember. I’ve probably deleted 4,000 words over the past two weeks. Part of this is because for the past week I’ve had this terrible fever thing and half of what I wrote was rubbish. The other part is because no one could have expected this record, and if you claim you did expect it, then you’re a liar.

I believe in The Wonder Years. I believe they are one of the most exceptional bands around right now. They showed us with The Upsides that they could connect to young adults on a fiercely intimate level — more impressively than many of their peers from the late-2000s pop-punk revival. They showed us with Suburbia I’ve Given You All and Now I’m Nothing that not only was their arrival not a fluke, but that they possessed a critically important trait — the ability to, as a group, gather themselves and write an album that both drew upon and grew away from their previous triumph, and improved upon it in every measurable way.

I believe in The Wonder Years. And that’s why I’ve continued to place unrealistic expectations on them. It’s because they haven’t yet done anything less than wholly impressive — nothing that has told me I shouldn’t expect the next thing to be better than the last thing. They’ve earned my trust and my expectation.

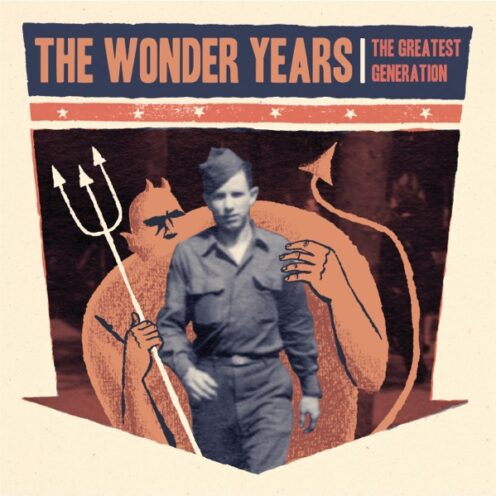

But with The Greatest Generation, The Wonder Years wrote a better record than I thought they were capable of. They eclipsed themselves. The progression we see here is something we can now consider methodical, but hardly something that we should take for granted or be any less impressed by. Between The Upsides and Suburbia, there was an exponential leap in the definable qualities by which you judge a band — both the vocals and musicianship were improved upon dramatically. The jump was urgent yet natural, defining yet familiar.

Consider the growth between Suburbia and The Greatest Generation to be similarly exponential, as The Wonder Years are expanding outward in every direction while further mastering their craft. They have shown us their ability to connect via that fiercely strong lyricism, but now they’re showing us they have seemingly never-expiring longevity in the form of evolving raw talent and a penchant for making themselves better.

The first note to make about The Greatest Generation is that it expands this band’s sound in two different directions. There are pop-punk choruses here that are larger than this band has ever written (“We Could Die Like This,” “Teenage Parents” and the towering chorus in “A Raindance in Traffic”), but simultaneously the musicianship is expanded upon and evolved. Certain moments are quieter than this band previously knew how to play. The guitars are slashing, at times tinged with Midwestern influences, and the melodies infused with Nick Steinborn’s keys are crafted with new precision.

Opener “There, There” begins with frontman Dan Campbell perhaps singing more softly than he’s been able to in the past, and he’s barely above a whisper the first time he delivers, “I’m sorry I don’t laugh at the right times.” The rest of the band kicks in, as Mike Kennedy’s snare hits carry us through the song’s second verse. By the time it’s Campbell turn to deliver that line again, it’s in the exhaustively desperate yell/scream we’re all so familiar with as the guitars begin to bounce off each other. Even at just under 2:30, “There, There” packs a significant wave of music and a punch of emotion into the first song on the record; it both amps you up and settles you in for the rest of the ride.

The Greatest Generation is lyrically littered with five key recurring themes that drive the record’s narrative. We encounter the first of these themes, ghosts, in first single “Passing Through A Screen Door,” the song that sounds most similar to Suburbia. The track is solid throughout, but is at its most impressive musically in the bridge leading up to Campbell’s climactic cry of, “Jesus Christ, did I fuck up?” We’re presented with imagery of pill bottles on “Dismantling Summer,” a track highlighted by Campbell’s “What kind of man does that make meeee?” harmonies with Matt Brasch in the song’s midsection.

Sandwiched by those two is another gem in “We Could Die Like This.” The chorus of, “Operator take me home, I dunno where else to go / I wanna die in the suburbs / A heart attack shoveling snow, all alone / If I die, I wanna die in the suburbs,” is one that should be a regular at live shows once the band is in full swing on this record’s touring cycle. Perhaps the chorus is repeated once too often here considering there’s a thin bridge, but that’s forgiven by the jam-worthy chaos of guitar and drum carnage that lays the groundwork for the final refrain.

The Greatest Generation’s two fastest songs bookend its most interesting one. “The Devil In My Bloodstream” (there’s another theme) is something to analyze in its own right, a piece of songsmanship this band couldn’t have pulled off two years ago. Laura Stevenson provides beautiful accompaniment in her guest spot as she and Campbell croon over a piano ballad, then the track takes a dramatically hard turn as Campbell belts, “I bet I’d be a fucking coward / I bet I’d never have the guts for war.” Later, when the track is fully rolling, another soon-to-be fan-favorite one-liner is offered in the refrain of, “I know how it feels to be at war with a world that never loved me.” This song is essentially split in half into two separate entities, each with its own personalities but connected with lyricism…it’s an impressive feat of writing.

In contrast is the extremely fast, extremely happy-sounding “Teenage Parents,” which actually delves into a sober story about growing up in poverty. The track’s undoubted triumph is in its constant drive, pushed by Mike Kennedy, who took nearly every half-moment that might have been empty and inserted a drum fill. It kicks off the record’s B-side, one that’s anchored by three key tracks. The mid-tempo “Chaser” comes complete with a 21-second face-melting guitar solo from Nick Steinborn. “A Raindance In Traffic” has gang vocals galore that raise its chorus to skyscraper status and its haunting refrain of, “I used to have such steady hands / Now I can’t keep them from shaking” makes it all the more powerful. And “Cul-de-sac” successfully sets up the record’s closing number while giving us throaty Josh Martin yells in the chorus.

The record’s tail side is also where we see its only minor stumbles. “An American Religion” stands out to me after maybe a month of listening where “Summers In PA” stood out to me at a similar timeframe for Suburbia — not as filler, but as the one song that you *might* consider skipping. However, you’ll probably keep it on just to hear an ominous drum-and-bass portion driving the line, “Truman will always be remembered for dropping the bomb / I’ll always be remembered for my fuckups.” The acoustic “Madelyn” swings for another quiet number to join the same category as “There, There” and “Devil In My Bloodstream,” but could have benefited from some percussion to back up the very solid lyricism.

Regardless, The Greatest Generation ends on the ultimate high note. “I Just Want To Sell Out My Funeral” brings the songwriting bar to its highest level because depending on how you’re counting, this seven-and-a-half minute monster could be two totally separate songs strung together by a kick drum at the 3:26 mark, or it could count as 13 songs all exploded and then sewed back together very nicely. The track begins as its own individual song, one that reveals a personal crisis of Campbell (or, maybe, The Wonder Years) just wanting to have been enough for the people in his life before dying. Then the track switches gears into a reprise, recalling key phrases from previous songs into a jaw-dropping three-plus minute medley. The chorus of “Teenage Parents” gets wound with a one-liner from “Devil In My Bloodstream” at one point, just showing the creative songwriting that went into the process. As that melody comes to a close, the record folds with Campbell’s best lyrical verse as the frontman of this band:

I’m sick of seeing ghosts

And I know how it’s all gonna end

There’s no triumph waiting

There’s no sunset to ride off in

We all wanna be great men

And there’s nothing romantic about it

I just wanna know that I did

All I could with what I was given

The Greatest Generation is more personal than past Wonder Years records but in different ways. There isn’t a song about being in college and there isn’t a song about an ex-girlfriend. But there are a hundred little stories about discovering who you are, coming to terms with it and becoming the best version of yourself that you’re capable of being. About not settling for good and taking great instead. About doing the right thing. About becoming a great man or woman. It sounds pretty grown up, but we’ve accidentally grown up with The Wonder Years.

It is my firm belief that The Greatest Generation has no real precedent in this community. It’s my belief that there isn’t another band in pop-punk right now that can write a record this good. The Wonder Years are a band that will neither repeat the same records nor reinvent themselves for every album, but instead add in enough ingredients and weird ideas, go into any given room above an abandoned sandwich shop, and come out with a product that simultaneously still sounds like themselves and gives us enough new progression to chew on for another two years. All while getting better at being a band. That’s pretty remarkable.

In the video trailer for this record, Campbell says, “People say the greatest generation has come and gone, but they're wrong. They haven't seen what we're capable of.” Based on past experience, with high expectations getting shattered on an album-by-album basis, it’s possible we’ve only just started to see what The Wonder Years are capable of.

Devil in My Bloodstream

Devil in My Bloodstream