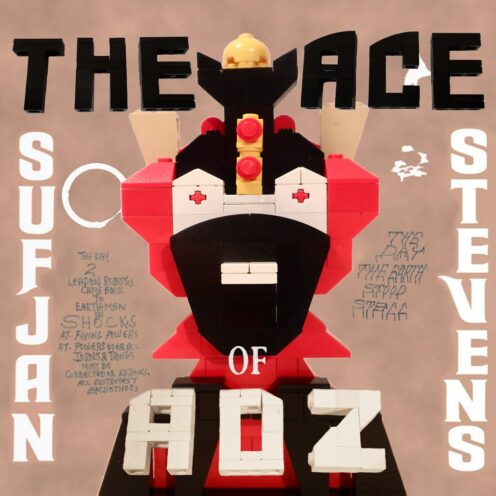

For a while, things didn’t look too good. It’d been five years since Sufjan Stevens released Illinois, the second album in his 50 States project, and fans hadn’t heard any news on the project – or his music- until sometime in 2009, when Stevens announced he was done with the project. Let’s be real, we knew he probably wouldn’t keep up with it, but wouldn’t it have been nice to hear a New York or Kansas album? Even more troubling than the demise of his project was the revelation that Stevens was thinking about quitting. Publicly questioning the mere purpose of creating music since albums were becoming obsolete due to downloading, Stevens just seemed disillusioned and tired. Thankfully, he found it within himself to release the All Delighted People EP earlier this year, shortly followed by the announcement that his sixth proper album, The Age of Adz, would be releasing in the fall. But fans were blindsided once again by Stevens once Adz traveled into ear canals everywhere. The 50 States project wasn’t the only thing that got left behind this year, as Stevens’ brand of folk is nowhere to be found outside of the deceiving opening track (“Futile Devices”). Instead, Stevens has rebuilt himself and his music with new themes, glitchy electronics, booming drums, Auto-tune, and more.

Although Stevens has abandoned his 50 States project, he hasn’t stopped playing to a concept, as Adz is loosely based on the imagery and work of American artist and schizophrenic “prophet,” Royal Robinson. Some of the album’s inspiration comes from the eccentric, bold, and vengeful work of Robinson, which is quite telling of the album as a whole, as well as Stevens’ mindset. Forever we’ve painted Stevens as the choir boy in the indie scene, a picture which he seems set dead on tearing down. The first instance is the regret-filled “Too Much,” which is paced by layers upon layers of electronics, giving off a definite Kid A vibe throughout. Lyrics about love lost, religion, death, and the like litter the album, as The Age of Adz features his most personal yet abstract work to date. Bitterness flows throughout the electro-pop of “I Walked,” as Stevens’ delicately states, “At least I deserve the respect of a kiss goodbye,”while he questions what he thought was love (“Somewhere I lost whatever else I had”) on the haunting, hymn-like “Now That I’m Older.”

Stevens has a knack for huge songs of grandeur, and that isn’t lacking here. The title track sounds like a robotic exodus is on its way, while the fantastic “Get Real Get Right” definitely sounds like something that just fell out of orbit. He channels his inner LeBron James by referencing himself in the third person on the gentle “Vesusvius,” a reference to the volcano that laid waste to the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. In fact, he makes this tale incredibly personal, going as far to suggest that he is Vesuvius (“Sufjan, the panic inside, the murdering ghost that you cannot ignore”).

The biggest shock comes in the form of the penultimate track, “I Want To Be Well,” a quirky, fast-paced track that harbors dark feelings. In what may go down as Stevens’ most personal track ever, it’s a veritable journey into the depths of his mind, his creative doubts, the unwanted recognition as indie rock’s golden child, or a rotten relationship. He’s never been this vulnerable, intimate, or provoked in his career, as his anger, doubt, and threats come to a head when Stevens’ sneers, “I’m not fucking around” nearly 20 times, which is a truly startling moment. The final track, “Impossible Soul,” is a 25 minute, five-part epic that delves into the issues the previous track presented. Any sort of instrument or vocal technique you can think of – guitar, horns, the electronics, orchestra, harps, choirs, auto-tune, call and return vocals, etc. – is thrown into this gigantic song. Only an artist as renowned and ambitious as Stevens could pull this off, which he does in glorious fashion. Despite the harrowing nature of the lyrics throughout this song (and album), Stevens ends The Age of Adz seemingly well-adjusted, realizing that there is peace and hope at the end of the dark tunnel by stating, “Boy! We can do much more together! It’s not so impossible,” only to contradict that thought by quietly ending the album with, “Boy, we made such a mess together.”

While most of the initial focus on The Age of Adz will be on the electronic transformation Stevens’ music has gone through, it will soon take a back seat to his complicated narrative, which exposes himself as an insecure, failed lover who has just as many doubts as us. Musically and lyrically, The Age of Adz is exhilarating, challenging, and thought-provoking. Sufjan Stevens may be more jaded about the state of music and himself than he was five years ago, but thankfully he can still take himself and his listeners on such thrilling sonic adventures, whether it’s through the Midwest or his own mind.

Impossible Soul

Impossible Soul